Amon: The King Who Refused To Repent (2 Chronicles 33:22–23)

You come to this story expecting judgment and maybe mercy, because that’s what kings in Judah usually promise you: spectacle, holiness, collapse, or rescue. Amon is different because he’s small and quick and stubborn in a way that makes you uneasy. He rules for two years and then he’s dead. The chronicler tells you his age, his mother’s name, that he did what his father did, and that he refused the soft, humiliating arc of repentance that the same book later gives to his father Manasseh. The verses that name him are short; the questions they expose—about responsibility, memory, and the possibilities of change—stay long.

Read the baseline portrait here: 2 Chronicles 33:22–23. Those lines are a simple thing, but you quickly learn they sit inside a wider drama about kings, idolatry, national identity, and the way memory is written into scripture.

Why you should care about Amon

There’s a temptation to skip over Amon because his reign is short and seems uninteresting beside the larger arcs of Manasseh or Josiah. But if you look, Amon stops being a mere footnote and becomes a mirror. He shows what happens when continuity of sin becomes a way of life, and he’s a counterpoint to the surprising reversal of his father. You’ll want to read the few verses about him carefully because they compactly reveal theological and literary choices: who the chronicler wants to praise, who to condemn, and how repentance is framed as a meaningful possibility—except when a person refuses it.

If you go back a few verses you’ll see the chronicler’s fuller design: 2 Chronicles 33:1–21. That section lays out Manasseh’s sins and his eventual humiliation and repentance. Then the verses about Amon interrupt that movement.

The immediate portrait: what the text actually says

You can’t get away from the bluntness. Amon was twenty-two when he began to reign, and he reigned two years in Jerusalem. He did evil in the sight of the Lord, as his father Manasseh had done; he sacrificed to the carved images his father made and served them. The chronicler doesn’t sugarcoat or extend. You get facts: age, length of reign, moral evaluation, religious behavior. Read it: 2 Chronicles 33:22–23.

Those details are all functional. Age and years anchor you historically; the comparison to Manasseh emphasizes continuity; the specifics of worship—sacrifices to carved images—place Amon squarely in a recognizable category of illicit religious practice. The chronicler isn’t doing psychological probing here; you get legal and ritual description.

The political outcome stated plainly

The chronicler also tells you what happens to Amon and why: servants conspire and assassinate him, and the people then make Josiah king, who is only eight. The short account is available at 2 Chronicles 33:24–25. It’s sudden, like someone who won’t relent and then is brought down by the very network that enabled him.

That you’re told Amon was murdered by his own servants matters. It suggests that his rule was not stable, that his authority had eroded, and that the social order in Jerusalem was brittle. The text leaves you to decide whether this is poetic justice, political necessity, or simply the way personal obstinacy ripples outward in a small polity. You’re inclined to read it as all three, because the chronicler wants you to. The narrative offers no consolation: there’s no repentance, no return, no restoration for Amon.

Amon in the wider scriptural context: echo and difference

If you want perspective, you have to look at 2 Kings and the rest of Chronicles. The books of Kings give you a more curt and less reflective account. Read Amon in 2 Kings here: 2 Kings 21:19–26. The facts are similar—short reign, evil, assassination by his own servants—but the chronicler’s placement of Amon next to Manasseh’s repentance shades the meaning differently.

Manasseh’s life is essential background because it’s where the theme of repentance is introduced and dramatized. In Chronicles, Manasseh is a long-term villain who experiences exile, humiliation, and then returns to the Lord in prayer, leading to restoration: 2 Chronicles 33:12–13. The chronicler seems intent on showing that even the worst king can repent and be restored. Amon refuses this movement. You can see the chronicler making a theological point: repentance is possible, but it depends on the human will.

It matters that Chronicles is written with a theological and liturgical agenda. The chronicler edits the traditions to highlight return and reform. So Amon’s refusal to repent becomes, in that context, a warning. Where his father’s repentance can be taken as an argument for God’s mercy—even in extreme cases—Amon’s refusal points to the moral responsibility that remains with each person.

You and the moral vantage point

When you read these texts as a reader now, you’re aware that scripture is not trying to be unbiased history the way a modern historian would try to be. The chronicler has a community in mind—post-exilic Judah—trying to instruct how to think about kingship and worship. So when the chronicler gives Manasseh repentance but denies Amon that arc, he’s making a choice meant to influence the reader: choose repentance, and your nation may be spared. Refuse it, and the cheap death of Amon will be evidence enough of the consequences.

Literary structure and character contrast

The chronicler arranges material to create contrasts. Amon follows Manasseh but precedes Josiah—a line that looks like ruin, stubbornness, and then reform. Read the passage that introduces Josiah’s kingship: 2 Chronicles 34:1. Josiah is the sun after a short eclipse, a child who will become a reformer.

This structure is not accidental. You can sense the chronicler doing the work of pairing stories so the theological point lands: Manasseh is the worst who repents; Amon is brief and condemned; Josiah is the righteous reformer whose rule will mark a turning point. The sequence functions more like moral pedagogy than biography.

How the chronicler’s style shapes your response

The chronicler uses summary statements—“he did what was evil in the sight of the Lord”—rather than extended narrative. Those statements are meant to do moral heavy-lifting. They force you to read quickly between the lines and infer the social and religious consequences. That technique makes Amon’s refusal feel not like narrative laziness but like a moral accent: his lack of repentance is not a drama to be unpacked; it is a principle to be taught. You can feel the chronicler’s finger tapping on the table.

Religious behavior: what Amon actually did

The text tells you he sacrificed to the carved images his father had made and served them: an explicit continuation of Manasseh’s cultic policies. The chronicler fastens on idolatry, because it’s the litmus test for faithfulness in their theology. Read the context of Manasseh’s idolatry back in Chronicles: 2 Chronicles 33:1–9. The repeated phrase “he did evil in the eyes of the LORD” in Chronicles is not casual judgment—it points to covenant infidelity and ritual corruption.

When you think about what that actually looked like on the ground, you imagine sanctuaries repurposed, altars rebuilt, people coerced or persuaded into participating. The phrasing “sacrificed to the carved images” suggests formal cult practice, not private superstition. It’s a public, state-sponsored affair. That matters because the chronicler’s interest is communal restoration; when the state leads the people into idolatry, the whole covenantal structure breaks down.

Ritual and political power

You should notice how ritual and political power are entangled. Idolatry is not merely theological errancy; it’s a symbolic politics. Kingship in ancient Judah was performed through rituals that confirmed the king’s authority and his relationship with the divine. So when Amon continues his father’s cult—whose apparatus had been established to consolidate power—he isn’t simply wrong in belief; he’s acting to preserve a political order that depends on certain religious expressions.

It’s helpful to read the parallel description of Manasseh’s policies in Kings, which mentions building altars and setting up policies: 2 Kings 21:1–18. There you see what “doing evil” might entail in administrative and cultic detail.

The assassination: social breakdown or moral consequence?

Amon’s death at the hands of his servants reads like a small, private tragedy that also tells you about the social order in Jerusalem. The chronicler gives you the bare facts: conspiracy, assassination, and then transfer of monarchy to a child. Read it again: 2 Chronicles 33:24–25.

You can choose to read that sequence in different ways. One is as moral consequence: Amon’s refusal to repent led to internal division and the violent end of his reign. The chronicler loves moral causality—sin brings ruin. Another is as political reality: court intrigues are real, and kings who lose the elites’ support are more vulnerable than empty rhetoric might suggest.

Either way, you feel the chronicler turning the anecdote into a lesson about governance. The assassination proves that complicit culture cannot sustain itself indefinitely. The regime decays from within because the rituals that hold it together—the ones Amon performs—can’t secure loyalty when the political stakes shift.

You thinking about empire and memory

Amon’s brief reign and his violent end are the kind of tidbit that shapes collective memory. It’s not a sweeping narrative of doom; it’s a short, sharp discontinuity. That sharpness is useful in a post-exilic community trying to decide what to keep and what to reject. You see why Chronicles chooses to compress Amon the way it does: he’s an example for a community that must decide how to relate to its past, to its leaders, and to the possibility of reform.

Manasseh’s repentance and the contrast with Amon

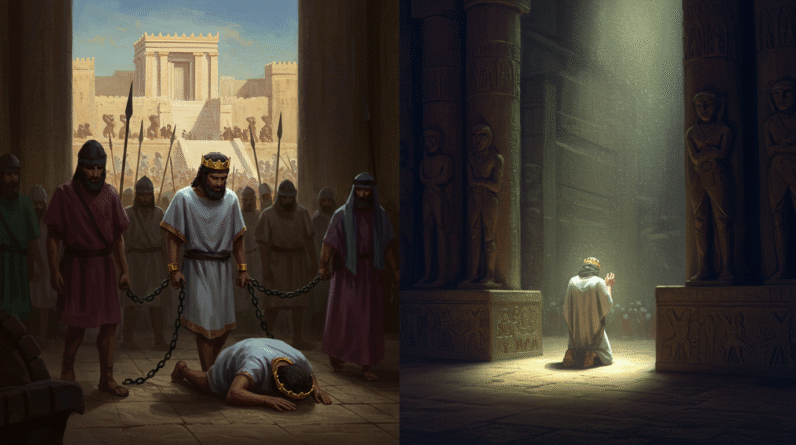

To understand the force of Amon’s refusal, you have to look at Manasseh’s surprising repentance in Chronicles: 2 Chronicles 33:12–13. The chronicler has Manasseh captured and taken to Babylon; he prays to God and is returned to Jerusalem, after which he reforms. The theological point is thick: God’s mercy is available even to the worst offender.

Amon undermines that optimistic theology by refusing to be transformed. You’re left with the uneasy truth that scriptural hope is conditional: it’s not merely the existence of divine mercy but human acceptance of it that determines outcomes.

Two models of human agency

When you look back at both cases together, two models of agency appear. Manasseh acts, belatedly, to turn toward God; his story functions as a parable of possibility. Amon acts by doubling down; his story functions as a parable of refusal. The chronicler wants you to hold these together. The message is not deterministic. It’s ethical: you are responsible for receiving or rejecting the possibility of change.

That’s a chilly lesson when you think about your own life, because it subtly shifts blame and credit back to you. You may be comforted by divine mercy, but you are also the one who must accept it.

Historical and scholarly caution: what you can and can’t claim

You probably want to know whether these accounts are historically reliable or later theological editing. It’s wise to be cautious. Chronicles was written with a community and agenda in mind; its purpose is theological history, not modern historiography. So you can’t treat every narrative detail as factual in the modern sense. Instead, treat Chronicles as a document that preserves memories refracted through theological concerns.

For the more straightforward chronological data—like ages and reign lengths—you can assume the chronicler was working from court records or royal annals. For interpretive matters—why a king is judged good or evil—you should read the chronicler’s evaluative categories as theological commentary.

If you want the contrasting accounts, consult the parallel in Kings for comparison: 2 Kings 21:1–26. Kings gives you the rawer, perhaps less reflective version; Chronicles reshapes the material to fit an agenda of restoration.

Archaeology and context

Archaeology can sometimes help reconstruct the cultural and political settings—temples, altars, inscriptions—but it rarely settles the question of individual repentance or moral judgment. You should keep that difference in mind: archaeological data complements textual analysis but doesn’t nullify a text’s theological purpose.

Theological themes you’ll notice

The story of Amon raises several theological themes that matter if you’re interested in how scripture addresses sin, repentance, and national fate.

- Covenant fidelity: Amon’s primary failure is uprooting the covenantal norms that define Israel/Judah’s identity. The chronicler frames this as a betrayal of the community’s relationship with God.

- Human responsibility: The text gives you responsibility. Manasseh’s later repentance is proof that God’s mercy is real; Amon’s refusal is proof that mercy alone isn’t enough.

- Memory and choosing the past: The chronicler curates memory to instruct the present. Amon’s brief, condemned reign is part of that curation.

- Political theology: State religion is not neutral; the king’s religious choices define the polity’s spiritual destiny.

Those themes aren’t pious abstractions. They map onto social realities: whether priests can be trusted, whether rituals will be performed correctly, how foreign influence will be handled, who will be allowed to officiate.

How those themes matter for you now

You might assume these concerns are distant, but they’re not. The questions chronicled in this short reign—how leaders model behavior for a community, how memory is curated for the future, how repentance functions—are still contemporary. When you think about politics or leadership today, consider how small decisions become paradigmatic, and how the ethical stance of those in power can affect whole communities.

Reading Amon devotionally, morally, politically

You can’t read Amon in only one register. If you read him devotionally, you find a cautionary tale: don’t harden your heart. In moral terms, Amon is the person who refuses corrective humility. Politically, he is a symptom of a polity that has failed to institutionalize repentance and reform.

If you read Amon psychologically, you might ask why someone raised in a corrupt court would choose to perpetuate the system. The text doesn’t offer a psychology. But you know that power, habit, and the incentives of royal courts create incentives to preserve the status quo. That’s not a theological excuse; it’s a social diagnosis.

Amon as a mirror for your own stubbornness

The chronicler is not only speaking to kings. The book addresses communities and individuals. You can’t help imagining yourself: would you turn when humbled? Or would you double down? Amon’s example provokes some personal accounting, even if you’re not a monarch. The story’s moral pressure will sit with you.

Literary aesthetics: why the chronicler’s brevity works

The chronicler’s crispness with Amon creates an effect. Because the account is short and unsympathetic, it leaves space for the reader’s moral imagination. The lack of psychological detail encourages you to fill in motives and consequences. In another hand, a longer narrative might have invited exculpation or explanation; here you get judgment.

That economy is an aesthetic decision. It’s quiet and somewhat severe. It mirrors the way the chronicler treats other kings who don’t reform: people who refuse God’s correction are not given elaborate backstories; they are simply named, judged, and mostly forgotten—except as warnings.

The interplay of narrative and admonition

The narrative form alternates with didactic sentences. The chronicler summarizes moral conditions and then gives short narrative sequences to illustrate his point. You can sense the pattern and anticipate the moral message: God’s people must return to covenant practices, and kings who obstruct that process are to be judged harshly.

What modern readers often miss

You might read the story as an ideological artifact that only matters to ancient Israel. But you’re missing the broader human pattern. Amon is about how small choices compound when they’re made by leaders who aren’t corrected. It’s also about how communal memory works—the chronicler preserves some parts of the past to teach another generation.

Many readers also miss the subtlety that the chronicler’s portrait of Manasseh is intentionally redemptive. That makes Amon’s refusal more dramatic. The chronicler believes in second chances—but not in inevitability. That’s an uncomfortable theological stance for contemporary readers who may expect simplistic assurances: God forgives, therefore everything will be fine. The chronicler refuses simple moral complacency.

Practical takeaways you can carry with you

When you leave this story, you might keep a few practical lessons in mind:

- Leadership matters: ritual and symbolic actions by leaders shape community behavior.

- Repentance is both divine offer and human assent: the possibility of a second chance doesn’t erase the need for personal response.

- Memory is taught: religious communities control collective memory by what they choose to commemorate and condemn.

- Small reigns can teach big lessons: brevity in narrative can sharpen moral instruction.

These are not platitudes; they are the ancient world’s way of instructing a fragile, post-exilic community—and they still have purchase when you consider leadership, responsibility, and moral choice in your own life.

Final reflections

You finish the passage and you feel a certain dissatisfaction because Amon’s story is unsatisfying—he doesn’t repent, there’s no dramatic redemption, and the narrative moves on quickly. That dryness is the point. The chronicler isn’t telling you a story to entertain; he’s presenting data for moral deliberation. The lack of a redemption arc for Amon is meant to sting. It asks you to consider whether you, or your leaders, would have chosen differently.

At the same time, the chronicler’s larger theology offers hope: Manasseh’s repentance reminds you that change is possible. But hope requires you to act. That’s the ethical pressure of the book. It’s not sentimental. It’s exacting and a little ruthless.

If you want to read further, contrast the Chronicler’s emphases with the accounts in Kings: 2 Kings 21:1–26. Then read Manasseh’s repentance again: 2 Chronicles 33:12–13. Sit between those texts and ask what you would choose if you were a king, or a member of a court, or simply someone with the power to change the small rituals that shape your community.

Explore More

For further reading and encouragement, check out these posts:

👉 7 Bible Verses About Faith in Hard Times

👉 Job’s Faith: What We Can Learn From His Trials

👉 How To Trust God When Everything Falls Apart

👉 Why God Allows Suffering – A Biblical Perspective

👉 Faith Over Fear: How To Stand Strong In Uncertain Seasons

👉 How To Encourage Someone Struggling With Their Faith

👉 5 Prayers for Strength When You’re Feeling Weak

📘 Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery – Grace and Mercy Over Judgement

A powerful retelling of John 8:1-11. This book brings to life the depth of forgiveness, mercy, and God’s unwavering love.

👉 Check it now on Amazon

As a ClickBank Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Acknowledgment: All Bible verses referenced in this article were accessed via Bible Gateway (or Bible Hub).

“Want to explore more? Check out our latest post on Why Jesus? and discover the life-changing truth of the Gospel!”