Josiah: The King Who Rediscovered God’s Law (2 Kings 23:1–2)

You come to this story thinking you know what to expect: a king, a scroll, a reform. But the narrative in 2 Kings pulls you into a quieter drama, the kind that happens when someone reads and then decides, almost against the grain of history, to change the way a whole people live. The moment is small — a scroll is found, a voice reads aloud — and yet everything about Judah shifts. Read the scene in the Bible and you’ll find the details laid out with a kind of bluntness that makes the moment feel both intimate and inevitable: 2 Kings 23:1–2.

Why this scene matters to you

You might think that this is an old incident, useful only to theologians or historians. But it touches something practical: how a community recovers or ignores its founding commitments, and what it looks like when leaders decide to make their words match their actions. Josiah’s rediscovery of the law shows you what reading together can do. It also strains against your assumptions about power — that kings change the world by sword or edict. Here, change begins with listening.

Setting: Judah after a long decline

You need to set the scene to feel the weight. Judah, the southern kingdom, has been through a cycle of kings, many of whom are indifferent or hostile to the covenantal law. The religious landscape is corrupted; altars and high places flourish, and the memory of what the law demanded is dim. This is not a clean slate. The people have been living with the effects of Manasseh’s reign and with long-standing compromise. The background explains why finding a scroll matters so much.

See the record of Manasseh’s policies and their consequences in the royal annals: 2 Kings 21:11–15. You’ll see, if you read it, the scale of the departure from covenantal practice and how that departure set the stage for Josiah’s later reforms.

The discovery: a scroll in the temple

You can almost imagine the scene: the temple, the religious officials, Hilkiah the priest. There is a kind of practical neglect of the sacred texts; they’re not read regularly, and the central archive has been neglected. Then Hilkiah finds “the book of the law” in the house of the Lord. The text accidentally resurfacing is an arresting image: the law itself, hidden or forgotten, re-enters the story and starts a conversation no one anticipated.

The discovery is described earlier in the narrative. Read the moment where Hilkiah finds the book: 2 Kings 22:8. The verses that follow explain how the text was brought to the king and how the king reacted. You’ll notice the word “discovered” is less theatrical here; it’s a slow revelation, an item reappearing in a place where the people had stopped looking.

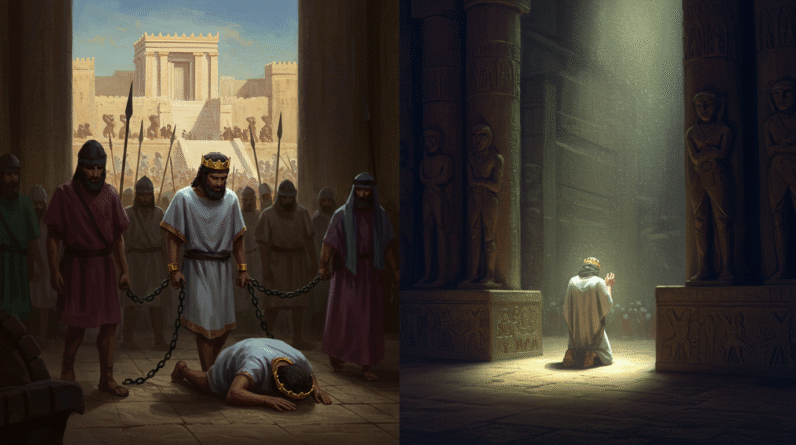

Josiah: a king who listens

You won’t find Josiah presented as a grand strategist. The text gives you a man whose distinctiveness is his responsiveness. When the book is read to him, he is shaken. It’s not because of political threat; it’s because the law exposes what his nation has become. He tears his clothes — a classic biblical gesture of grief and repentance — and he begins to act.

Read about Josiah’s reaction and what he decides to do next: 2 Kings 22:11–13. The narrative frames his response as a moral and religious awakening, not simply a political maneuver. In other words, you see a leader whose first move is to listen and lament.

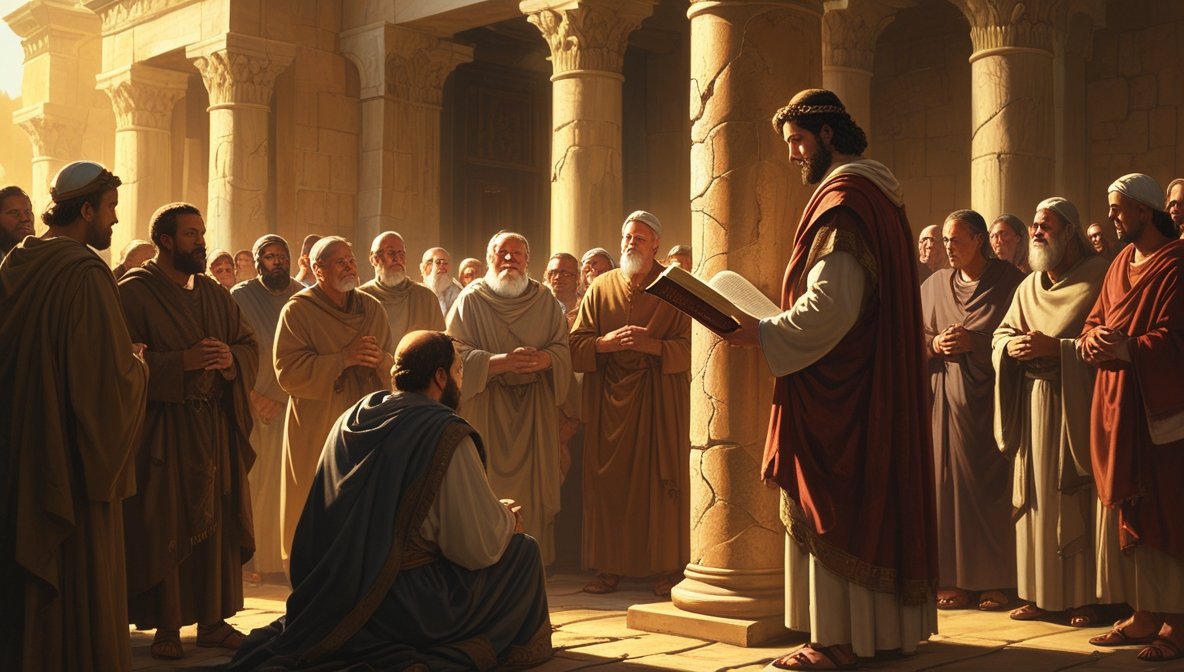

Public reading and covenant renewal (2 Kings 23:1–2)

This is the moment the title points to: the public reading of the law and the covenant that follows. Josiah summons “all the elders of Judah” and “all the inhabitants” of Jerusalem. The text makes a point of the communal nature of the act: this is not the king’s private devotion; it is collective memory being reactivated in public.

The passage itself puts it simply: read it here and see how deliberate the ritual is: 2 Kings 23:1–2. The king stands by a pillar to make a covenant before the Lord — a public posture, a formal recommitment. Think about the significance: when a leader recites a text before a people, the community is invited to remember and to recommit in a shared way.

The ritual and its ancient resonance

You should notice that Josiah’s actions have strong echoes of earlier covenant moments in Israel’s history. He is not inventing a new religion. He is trying to restore fidelity to norms remembered in the Torah, norms that had structured Israelite life: Sabbath observance, centralization of worship, care for the poor, prohibitions against idolatry. That’s why references to Deuteronomy are important for interpreting Josiah’s reforms — the rediscovered “book of the law” is closely aligned with Deuteronomic law.

Compare what Josiah does with instructions about public reading in Deuteronomy: Deuteronomy 31:9–13. In Deuteronomy, the law is to be read periodically so that whole generations remember the covenant. Josiah’s public reading fits that script — he’s bringing the law back into the life of the people in a way that the prophetic and Deuteronomic traditions would endorse.

How reading becomes reform

You might be tempted to think a text has power all by itself. It doesn’t. The text becomes effective because people gather to hear it and because leaders interpret and enforce it. After the reading, Josiah doesn’t stop at ceremony. He undertakes a program of reform that is explicit and severe: he removes altars, destroys objects associated with foreign worship, defiles the high places so they can no longer be used for idolatry, and renews the Passover celebration in a way that recalls earlier, purer practice.

The sweep of his actions is summarized across 2 Kings 23. If you want to follow his steps, read the fuller list of reforms: 2 Kings 23:4–25. Here you see the law read aloud and then made the basis for public policy. The reading is not an abstract liturgical act; it is a mandate.

The narrative in parallel: 2 Chronicles 34–35

You should read the parallel account in 2 Chronicles because it gives you different emphases. Chronicles often highlights temple-centered reform and priestly action. In the Chronicler’s version, the discovery of the book and its presentation to the king lead to a religious revival that is notably more priestly in tone. Hilkiah and other priests have a larger role in the narrative.

See the Chronicler’s account and compare the way the discovery and reforms are narrated: 2 Chronicles 34:14–33. The differences are small but telling. The Chronicler wants you to see the temple’s centrality and the priesthood’s role in reform. That helps you understand how memory and ritual operate differently across texts.

The limits of reform

It’s important that you don’t romanticize Josiah’s success. Reform under his rule was real, but it was not permanent. The political forces at work — the rising power of Babylon, the complicated loyalties of neighboring states, the social habits of a populace used to syncretism — are beyond one king’s capacity to change entirely. Josiah dies in battle, and within a generation, exile comes.

The text itself allows for this sober note. The reforms are sincere but fragile. Read the melancholic coda in Kings: 2 Kings 23:26–30. The story respects the limits of human action. You see that intention and commitment matter, but they don’t guarantee a permanent turnaround.

The law as a disruptive memory

What makes the discovery of the law disruptive is that it functions as memory made readable. The book, when read aloud, confronts the community with a standard it has been ignoring. In a way, the law is like a photograph of a relationship; once people see it, they remember what their covenant commitments looked like. That is destabilizing. It invites repentance, but it also creates political and social tension.

Deuteronomy frames law as not merely a set of rules but as a story of God’s saving acts and covenantal demands. Look at Deuteronomy’s opening instruction about teaching the law to Israel’s children as a communal habit: Deuteronomy 6:1–9. The law shapes identity over generations, and Josiah’s attempt to restore that identity requires both public proclamation and sustained institutional change.

Memory, power, and literacy

You should note the role of literacy and public reading in transforming society. When the text becomes public property — read aloud from a central place — it no longer belongs only to elites. The covenant language is accessible to everyone present. That matters for political theology: a text read in public shapes the city’s consent and creates a shared moral vocabulary.

You’ll find echoes of this in other biblical moments where public reading is central. The scroll acts as an anchor for communal identity. The practice of reading scripture publicly becomes a kind of technology for social memory.

What Josiah teaches about leadership

You can take several lessons from Josiah that apply to leadership now. First, leaders who listen can do structural good. Josiah’s initial posture is to hear and to be changed by the text; he doesn’t use the book as a prop. Second, leadership without institutions is brittle. Josiah paired his reforms with practical measures — priests sent to dismantle altars, statutes enforced, Passover celebrated properly. Third, the rhetoric of repentance matters; symbolic acts like tearing clothes and covenant-making can catalyze public realignment.

The narrative invites you to think less about charisma and more about fidelity. A leader’s job, here, is to reorient a people’s memory and to anchor policy in that memory. That’s an old-fashioned idea. But it’s effective because it’s about aligning story and practice.

Reform and humility

You should also notice the humility displayed. Josiah doesn’t claim prophetic insight beyond the text. He calls the priest and the scribe. He orders the law read and then acts based on what it says. That humility — the admission that the law might judge his people — is part of what grants him moral authority. In contemporary terms, you might say he models how leaders should submit their policies to fixed principles rather than reshaping principles to fit preferences.

The humility is not passive. It is active obedience. Read the decisive covenant-making moment that bridges personal repentance and public policy: 2 Kings 23:3. The covenant is a deliberate move: it documents the commitment and binds the community to a shared standard.

Theological implications

You could treat Josiah almost as a parable about God’s faithfulness: the text is preserved, and the God of the law reasserts claim even after years of neglect. Theologically, it suggests that God’s purposes endure through texts and institutions. That’s not a deterministic view — human response still matters — but it’s an argument for the resilience of covenantal patterns.

At the same time, the story complicates triumphalism. The reforms are incomplete, the kingdom falls, and yet the law remains. Theological reflection here often emphasizes the interplay between divine patience and human responsibility. You might read this as a story about how God gives people opportunities to reform, but also about how human communities frequently fail to sustain such renewals.

Look at the way later prophetic literature interprets and reinterprets covenant failure. Jeremiah and Ezekiel, writing in the context of exile, reflect on how covenant fidelity was lost. You don’t have to read them as only historical; they also speak to the perennial challenge of aligning practice with promise. If you want to see prophetic lament about covenant neglect, read passages like Jeremiah’s calls to repentance, which expand the theme present in Josiah’s story: Jeremiah 11:10–11.

Practical lessons for communities and individuals

You might be thinking: how does this map onto your life now? The immediate lessons are surprisingly simple. First, texts matter. You can’t be a community without shared texts that shape memory and identity. Second, rituals matter. The reading, the covenant, the Passover — these aren’t mere theatrics. They ground change. Third, leadership that listens and then acts can initiate meaningful reform.

For your community, that might mean bringing neglected practices back into circulation. For you personally, it could mean reading foundational texts — sacred, cultural, or ethical — until they unsettle you. You’ll find that genuine change often starts in the small, repetitive acts of reading, discussion, and public recommitment.

The danger of nostalgia

One caveat: you must avoid the trap of using “restoration” as an excuse to refuse change altogether. Josiah sought to restore an older covenantal practice, but he did so in a context that required judgment of idolatry and social reform. Restoration was not just nostalgia; it required critical action. When you look for precedents, be careful to distinguish between memory that helps and memory that traps you in something harmful.

Think about how the law functioned to protect the vulnerable and structure justice, not simply to preserve ritual for its own sake. Your restoration should aim at justice as much as at identity.

Literary and canonical dimensions

You should notice how the Deuteronomistic history (the editors who shaped Joshua through Kings) frames Josiah as a high point. The editors were interested in law, covenant, and the centralization of worship. Josiah embodies those concerns. His reforms fit the editorial program: when the law is known and followed, Israel prospers. When it’s ignored, disaster follows.

Readers who pay attention to how the story is put together notice the editorial choices. The account of Josiah is unusually detailed compared to other kings. That detail is meaningful. It’s the narrator saying, yes, this matters. The law’s reappearance and the king’s response are not minor incidents; they’re central to the theological argument of the history.

The role of archives and memory work

Finally, you should care about archives. Hilkiah’s discovery is an archival moment. It’s about the preservation and retrieval of texts. This has analogues in your life: documents, stories, institutional memories. When archives reemerge, they can reorder priorities. If you manage a community, you should think about what you preserve and how you make texts available. If you don’t preserve memory, you risk repeating avoidable mistakes.

Consider how the Chronicler’s and the Deuteronomist’s interests differ, yet both converge on the centrality of law and temple. That’s a reminder that multiple narratives about the past can coexist and that archives are not neutral; they’re curated.

A careful, not sentimental, model of reform

If you lean toward optimism, Josiah can encourage you: revival is possible. If you lean toward realism, the story keeps your feet on the ground: reform needs structures and must face entrenched opposition. The biblical narrative does not indulge in easy triumphalism. It shows the courage of a king who listens and acts, and then the fragility of human institutions.

You’re left with a mixed verdict. That’s probably right. The story refuses to let you be naïve or purely cynical. It asks you to do the slow, hard work of reading, remembering, and then acting in a way that matches your public words.

What to read next

If the story has piqued you, pursue the surrounding chapters and parallels. Read the discovery in 2 Kings 22 and then the fuller account in 2 Kings 23. Compare with Chronicles. Read Deuteronomy for the law’s content and Israel’s covenant theology. For the discovery itself: 2 Kings 22:8–13. For the public reading and reforms: 2 Kings 23:1–3 and 2 Kings 23:4–25. For the Chronicler’s take: 2 Chronicles 34:14–33. For the broader covenantal background: Deuteronomy 6:1–9 and Deuteronomy 31:9–13.

Final reflections

You end up in a quiet place after reading Josiah’s story. It’s not a place of rousing slogans. It’s a place of attention. The rediscovery of the law is an occasion for listening, for public reading, for covenantal recommitment. It’s also a sober reminder that change is fragile and that institutions and stories matter because they are rehearsed, taught, and enforced across time.

If you take anything from this, let it be this: small moments of retrieval — a book found, a law read aloud — can have outsized effects, but only if they are followed by sustained practice. You can reproduce that pattern in your own life and communities. You can also be realistic about the limits and the need for institutions that outlive charismatic moments.