From Scrolls To Scripture: How The Bible Came Together

You may have wondered, at some point in your life, exactly how the Bible came to be the book it is today. “How the Bible came together” is a question that touches history, faith, scholarship, and devotion. You hold in your hands—or on your screen—a collection of writings spanning centuries, written by many hands in different languages, preserved through meticulous copying, and treasured by communities who believed these words were not merely human but divine. This article will walk you through that remarkable journey, tracing how oral traditions became scrolls, how scrolls became codices, and how those texts were recognized and preserved as Scripture. As you read, you’ll meet the key moments and decisions that shaped the Bible you know, and you’ll discover why this process matters for your faith today.

The First Steps: Oral Tradition and the Move to Writing

You need to remember that the earliest stories that would later be part of the Bible often began as oral tradition. Families and communities told and retold stories about God’s deeds, covenant promises, and acts of deliverance around hearths and at festivals. These narratives shaped communal memory and identity long before any scribe put ink to parchment. The move from oral to written form was not an abrupt leap but a gradual process where the spoken word found stability in written records.

One clear biblical indication of this transition is found in the instruction to write down the law. Moses and the leaders were commanded to preserve God’s instructions in written form so the people would remember and obey (see Deuteronomy 31:9). That command shows you the beginning of institutionalized preservation: God’s revelation was meant to be recorded and handed on. The oral stories that formed the backbone of Israel’s faith were now captured as documents that could be read aloud, studied, and taught.

The Torah: The Foundation of the Old Testament

When you ask “How the Bible came together,” you can’t start without the Torah—the first five books commonly attributed to Moses. The Torah formed the theological and legal foundation for Israel’s life: creation, covenant, law, and pilgrimage toward the Promised Land. Because of its central role, the Torah was carefully copied, read publicly, and safeguarded by priests and scribes.

You can see how central the Torah was in the life of Israel when you read accounts of public reading and instruction. In the post-exilic period, leaders read the Scriptures aloud and explained them to the people so they could understand God’s words and apply them (see Nehemiah 8:8). Those public readings show you a community committed to knowing and obeying what God had revealed—an essential step in how the Bible came together as a formative text for worship and identity.

The Prophets and the Writings: Expanding the Canon

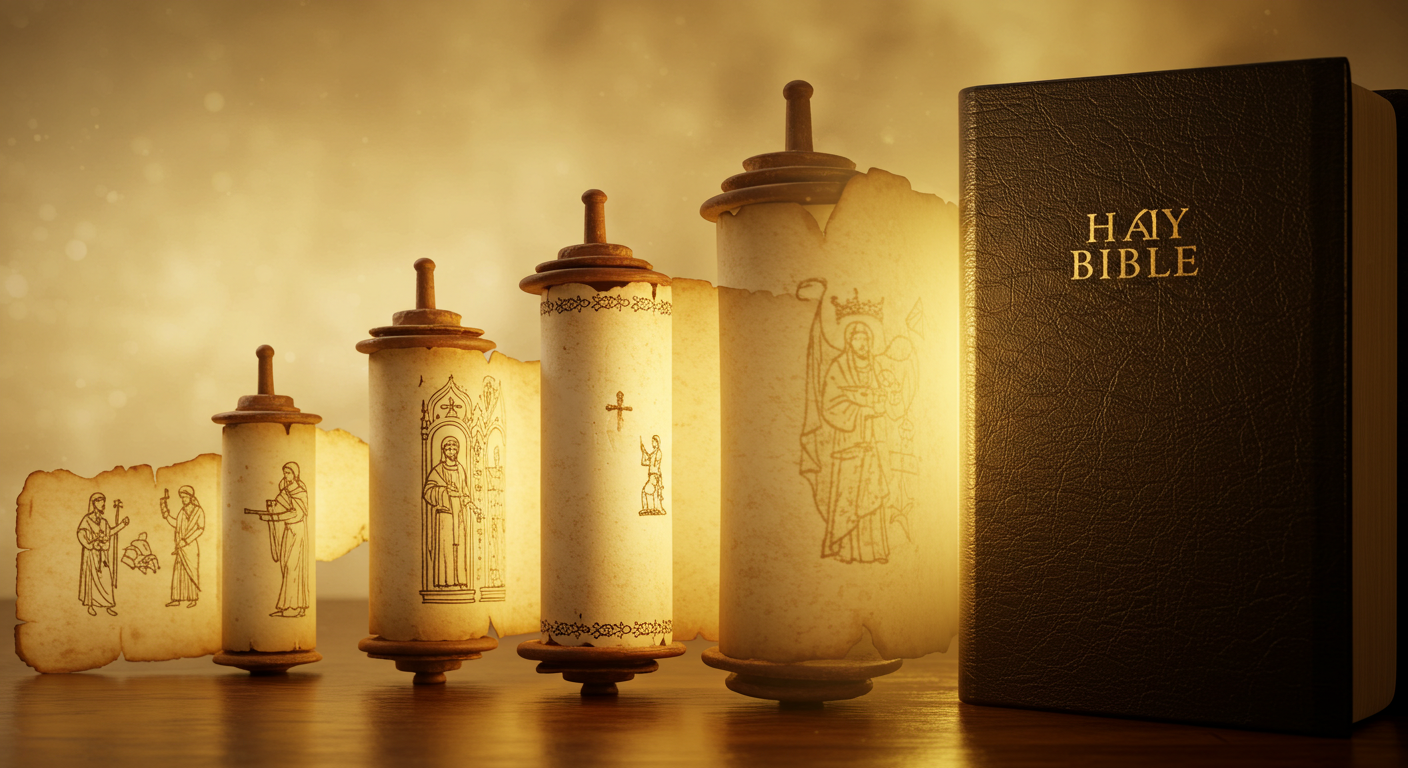

Beyond the Torah, other collections of books took shape—the Prophets and the Writings. The Prophets included histories and prophetic books that interpreted Israel’s story, while the Writings embraced poetry, wisdom literature, and later narratives. These books were not organized into a single volume at first; rather, they existed as separate scrolls treasured for their insight into God’s dealings with his people and the moral and spiritual lessons they contained.

You’ll see throughout the Old Testament how these writings were read, preserved, and treated as authoritative. The psalmist declares that God’s word is a lamp to your feet and a light to your path (see Psalm 119:105). That image captures the early conviction: these writings were more than history—they were the guide of life itself.

The Role of the Septuagint and the Diaspora

As Israel’s people spread into the Greek-speaking world, especially after Alexander the Great’s conquests, there came a need for Scripture in the language of the people. That need produced the Septuagint (LXX), a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. The Septuagint became the Bible for many Jews living in the Diaspora and later for the early Christian community. It’s one of the reasons you’ll find certain Old Testament quotations in the New Testament that reflect the Septuagint’s wording.

Luke’s description of Jesus reading in the synagogue illustrates how Scripture moved across languages and cultures. Jesus stood, read from the scroll, and explained its meaning, showing that the Scriptures were intended to be read aloud and applied (see Luke 4:17-21). The Septuagint helped people outside of Palestine have access to these sacred texts, which is a crucial part of “How the Bible came together” in a multicultural, multilingual world.

Copying and Preservation: Scribes, Masoretes, and the Dead Sea Scrolls

If you care about the authenticity of Scripture, you should know about the painstaking work of scribes who copied texts by hand through generations. Scribes took their duty seriously; any copying error could alter a text that communities believed belonged to God. You find traditions and techniques that aimed at preserving accuracy—counting letters, copying with meticulous care, and using checks and balances that passed on texts faithfully.

Centuries later, Jewish scholars called the Masoretes added vowel markings and notes to the Hebrew text to preserve pronunciation and precise readings. Meanwhile, in the 20th century, the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls gave you remarkable confirmation: many of the biblical texts from Qumran closely match the later Masoretic Text, demonstrating continuity in transmission. Scripture itself promises endurance: “The grass withers and the flowers fall, but the word of our God endures forever” (see Isaiah 40:8). That promise is not only spiritual reassurance—it’s bolstered by historical evidence of careful preservation.

You also read the Bible’s own affirmation of the Lord’s words being flawless and preserved: “And the words of the LORD are flawless, like silver purified in a crucible” (see Psalm 12:6-7). Those texts reflect a confidence that the message would be kept and handed down with faithfulness.

The New Testament: From Eyewitness Testimony to Written Records

When you turn to the New Testament, the question “How the Bible came together” leads you to apostolic testimony and early Christian writings. The Gospels began as accounts rooted in eyewitness testimony and community preaching about Jesus—his life, death, and resurrection. Luke explicitly states his intent to compile an orderly account from those who were eyewitnesses and servants of the word (see Luke 1:1-4). That desire for reliable testimony is exactly what you’d expect when a community seeks to preserve its foundational story.

Paul’s letters circulated between congregations and were read aloud, copied, and treasured. The early Christians treated these letters as authoritative instruction for doctrine and life. You see this recognition in 1 Thessalonians, where Paul’s words are described as “the word of God” because the recipients recognized divine truth coming through him (see 1 Thessalonians 2:13). Over time, these letters—together with the Gospels and other writings—formed the core of the New Testament collection.

Criteria for Recognizing Scripture: Apostolicity, Orthodoxy, and Use

You might ask, who decided which books belonged in the New Testament? There was no single moment when a magic list was produced and universally accepted. Instead, early Christians used several practical criteria when discerning authoritative books. They looked for apostolicity (a connection with an apostle), orthodoxy (agreement with the rule of faith and teaching about Jesus), catholicity (widespread use in churches), and antiquity. Books that met these marks were received and read in the churches.

Peter’s recognition of Paul’s letters shows how even early leaders accepted apostolic writings as part of the community’s instruction, though he also warned that some of Paul’s points were hard to understand but were being twisted by those who misunderstood (see 2 Peter 3:15-16). That passage illustrates both the authority attributed to apostolic letters and the pastoral care needed to apply them rightly.

Public Reading and Acceptance: How Communities Shaped the Canon

The churches exercised a practical role in recognizing Scripture. When congregations read certain writings regularly and found them edifying and consistent with apostolic teaching, those writings gained credibility. The early church councils—though they didn’t create the canon out of thin air—confirmed what the churches already recognized. Councils in Hippo and Carthage, for instance, gave official lists that reflected the consensus of Christian usage in the wider Church.

This communal discernment mirrors how Scripture itself was meant to function. Jesus and the apostles expected Scripture to be read, interpreted, and applied in communities. The early practice of public reading and teaching was not just tradition; it was central to how the Bible came together as a living library for worship, instruction, and daily life.

Textual Transmission: Manuscripts, Variants, and Reliability

You may have heard about textual variants in the Bible and wondered whether these undermine Scripture’s reliability. The honest answer is that, like any ancient document copied by hand over centuries, there are thousands of manuscript variations. However, the vast majority are minor and do not affect core doctrines. Textual criticism is the discipline that examines manuscripts, compares variants, and seeks to reconstruct the most likely original text. It’s a meticulous and scholarly process that gives you confidence in the reliability of the modern text.

One reason for confidence is the sheer wealth of manuscript evidence. For the New Testament, thousands of Greek manuscripts, as well as early translations and quotations by church fathers, allow scholars to cross-check and verify readings. The Old Testament benefits from multiple textual traditions—the Masoretic Text, the Septuagint, and manuscript finds like the Dead Sea Scrolls—which together provide a robust picture of the biblical text over time.

The Bible itself points to the authority of Scripture in ways that underscore your trust. Jesus said that “Scripture cannot be set aside” (see John 10:35), and Paul wrote that everything written in the past was written to teach and encourage hope (see Romans 15:4). These verses remind you that the Scriptures were preserved to instruct and guide you in faith and life.

The Closing of the Canon: When Was the Bible Complete?

You’ll hear different dates and moments proposed for when the canon was “closed.” For the New Testament, by the end of the second century, most of the books now in your New Testament were widely acknowledged, and by the fourth century, church councils affirmed the collection broadly used today. The process was more a recognition than a legislative act: the books that had proved faithful and useful were affirmed as trustworthy and authoritative.

Even Scripture itself contains warnings against altering God’s word. The book of Revelation ends with a solemn admonition against adding to or taking away from the words of that prophecy (see Revelation 22:18-19). That warning reflects an ancient concern for the integrity of sacred texts—a concern you share when you value a Bible that faithfully communicates God’s revelation.

Translation and Printing: Spreading the Scriptures to the People

Once the biblical texts were preserved and recognized, translation became the next great step in how the Bible came together for the wider world. Translators took the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts and rendered them into Latin, then into the vernacular languages of Europe and beyond. The invention of the printing press dramatically accelerated the distribution of Scripture, making the Bible available in ways that centuries of hand copying never could.

The aim of translation and distribution was faithful communication. Your access to Scripture in your language is part of a long story in which communities sought to bring God’s word to life for ordinary people. The biblical mandate to teach and instruct, to meditate on Scripture, and to allow Scripture to shape life is realized more fully when you can read God’s word yourself.

Scripture in Your Hands: Authority, Inspiration, and Living Word

When you ask “How the Bible came together,” you are not merely studying an academic process—you are encountering a story of divine care. The Bible claims a source beyond human wisdom: it is “God-breathed” and useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness (see 2 Timothy 3:16-17). That claim has guided communities to treat these writings with reverence, to preserve them, and to pass them on.

It is important for you to see Scripture not as a museum piece but as the living word of God. Hebrews reminds you that God’s word is alive and active, able to penetrate the depths of your heart and revive your soul (see Hebrews 4:12). The processes of compilation, copying, and canonization were not merely academic—they were the means by which the living word was entrusted to people like you.

The Role of the Church: Reading, Teaching, and Guarding the Word

You belong to a tradition that reads Scripture within the life of the church. From the earliest days, the church gathered to read Scripture, to hear explanations, and to let the text shape worship and practice. Acts commends the Bereans for their eagerness to receive the message and their practice of examining the Scriptures daily to confirm truth (see Acts 17:11). That example encourages you to be both receptive and discerning—open to the Spirit and careful with the text.

The church also played a protective role, guarding the teachings handed down from the apostles and ensuring that the books read in worship were trustworthy. That safeguarding extended through copying, teaching, and communal discernment—each step contributing to how the Bible came together for you and your fellow believers.

Why the Historical Process Matters for Your Faith

Knowing how the Bible came together strengthens your faith. It shows that Scripture did not appear magically—it was formed in real communities, under the guidance of God’s Spirit, and preserved through generations who loved the Lord and his word. You can trust that the Bible you read today is rooted in an unbroken chain of testimony, careful copying, and communal affirmation.

Scripture itself points backward and forward—to its own formation and to its purpose. Jesus and the apostles quoted and appealed to Scripture as authoritative. You see Jesus teaching from the Scriptures and explicating their meaning for his listeners (see Luke 24:27). That continuity assures you that the Bible’s message is not merely ancient wordplay but God’s enduring guidance for life and hope.

Practical Steps: How You Can Engage with Scripture Today

As you reflect on “How the Bible came together,” you may want to know practical ways to engage with Scripture in your daily walk. Begin with consistent reading—set aside time to read a portion of Scripture each day. Study with humility and prayer, asking the Spirit to illuminate the text. Join a community or small group where reading and discussion deepen understanding and accountability. Use reliable translations and, when questions arise, consult trusted commentaries or pastors who can help contextualize difficult passages.

Remember the Bereans’ example: test what you hear against Scripture. Let God’s word shape your beliefs, your morals, and your witness to others. The whole point of knowing how the Bible came together is to draw you into deeper knowledge of God and a life transformed by his truth.

Final Reflections: From Scrolls to Scripture, a Divine Story

When you trace “How the Bible came together,” you find a remarkable mixture of human diligence and divine guidance. From oral stories to written scrolls, from careful scribes to the communal recognition of the canon, from translations to printed Bibles in the languages of the world—the story is one of faithful stewardship. The Bible’s formation was neither inevitable nor accidental; it was shaped by communities that believed the Scriptures carried God’s authority and by a God who preserved his word for generations.

The Bible’s power is not merely in its historical pedigree but in its ability to reach and transform your heart. You find in its pages the gospel story of Christ, who fulfills the Scriptures, and whose life and death, and resurrection give meaning to every book in that sacred library. As you hold Scripture, you hold a book that was painstakingly gathered, preserved, and entrusted to you so that you might know God, be shaped by truth, and be sent into the world with hope.

If you’ve read this far, you’ve taken a meaningful step in understanding “How the Bible came together”—a journey that invites both the mind and the heart. May your study deepen your love for God’s Word and your commitment to live by it.

Explore More

For further reading and encouragement, check out these posts:

👉 7 Bible Verses About Faith in Hard Times

👉 Job’s Faith: What We Can Learn From His Trials

👉 How To Trust God When Everything Falls Apart

👉 Why God Allows Suffering – A Biblical Perspective

👉 Faith Over Fear: How To Stand Strong In Uncertain Seasons

👉 How To Encourage Someone Struggling With Their Faith

👉 5 Prayers for Strength When You’re Feeling Weak

📘 Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery – Grace and Mercy Over Judgement

A powerful retelling of John 8:1-11. This book brings to life the depth of forgiveness, mercy, and God’s unwavering love.

👉 Check it now on Amazon

As a ClickBank & Amazon Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Acknowledgment: All Bible verses referenced in this article were accessed via Bible Gateway (or Bible Hub).

“Want to explore more? Check out our latest post on Why Jesus? and discover the life-changing truth of the Gospel!”