Jehoiachin (Jeconiah): The Exiled King In Babylon (2 Kings 24:15)

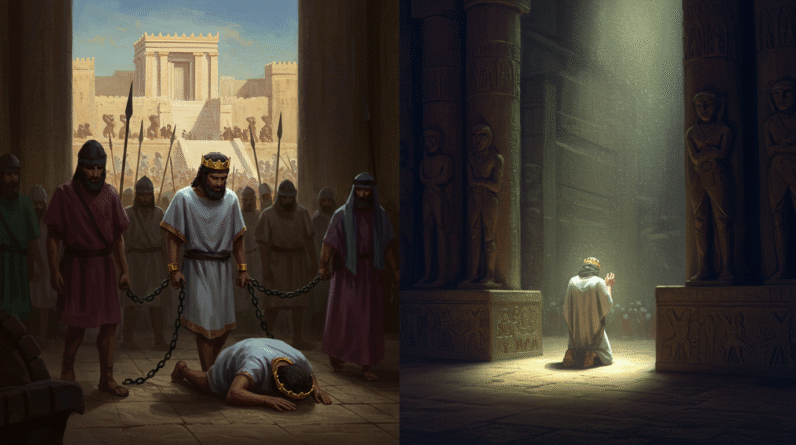

You come to Jehoiachin’s story expecting a neat moral or an easy hero. Instead, you find a young king on a throne too heavy for his shoulders, a city under siege, and an exile who becomes a small, stubborn thread in a history that refuses to be tidy. Jehoiachin (also called Jeconiah or Coniah in some translations) is a name that surfaces as a brief, almost embarrassed note in the chronicles of Judah. Yet when you look, his life is unexpectedly dense with political failure, theological dispute, and personal consequence. The central snapshot of his downfall is in 2 Kings 24:15, where the narrative compresses a catastrophe into a line: the king, his family, his officials, and many skilled people are deported to Babylon. Read it: 2 Kings 24:15.

You’ll want to pace the scene in your head: Jerusalem moored on its hill, the Temple’s shadow, the court’s hushed panic. Nebuchadnezzar’s army outside the walls. The story isn’t just political; it’s intimate. Jehoiachin is eighteen when he takes the throne (“he was eighteen years old when he became king, and he reigned in Jerusalem three months” — 2 Kings 24:8). Three months. You have to sit with that number. A reign measured in a single season, and then exile.

Where Jehoiachin fits: the historical frame

You probably already know that Judah’s last days feel like a long, slow collapse. The late monarchy era is a swirl of alliances, rebellions, and imperial interests. Egypt and Babylon loom; Assyria is withdrawn as a dominant force. All this is background noise to court intrigue and prophetic pronouncements. Jehoiachin appears at the center of a geopolitical climax: Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon asserts control, and the puppet strings tighten until they snap.

The biblical narrative situates Jehoiachin in a line of weak kings and failed reforms. He inherits a divided house: his predecessor, Jehoiakim, had been installed by Nebuchadnezzar, then rebelled; now Babylon returns. The chronicler’s language reads like reportage and lament simultaneously. For the scene of deportation, the books of 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles give you the official, ceremonial record: 2 Kings 24:8-17 and 2 Chronicles 36:9-10. They’re terse. They’re brutal. They’re oddly personal.

The young king and his brief reign

When you picture Jehoiachin, it helps to imagine what being eighteen on a throne meant then. Youth comes with a kind of rawness; it also comes with a hunger to prove yourself. The text doesn’t give him speeches or extended policymaking. You have the bare facts: ascendancy at eighteen, a three-month reign, surrender to Babylon. Read the starkness in 2 Kings 24:8.

The brevity of his reign is humiliating historically, but it’s also an aesthetic device. Biblical writers are often economical; they highlight the big shift rather than give you a play-by-play. So you’re left to infer: was the court incompetent? Was Jehoiachin manipulated? Were there immediate internal betrayals? The Hebrew chroniclers leave much unsaid, and that silence is part of the story. It presses you to fill in the human texture: the advisers who murmured, the generals who refused orders, the populace who watched the siege’s darkness approach.

The fall: siege, surrender, and deportation

You probably read 2 Kings 24 as a chronology of misfortune. The chapter gathers a series of blows: the Pharaoh’s withdrawal, Babylon’s vengeance, and then the deportations. It’s more helpful to linger over the deportation as a process, not an outcome. The text lists categories — “the king’s mother, his wives, his officials, and the prominent people of the land” — and it mentions the craftsmen and smiths who are valuable to an empire keen on absorption rather than mere destruction (2 Kings 24:15).

What’s important is that Judah’s elite is exported. Nebuchadnezzar does not simply kill resistance; he assimilates what can be useful and disperses what might later retake power. You should note the emotional cruelty of it: the family, the symbolic head of state, removed as a lesson but also as a practical repositioning of talent. You can sense a method in this catastrophe: a king is deported not only to be punished but to be neutralized, to carry the humiliation back as a living emblem of empire.

Read how the narrative frames it: the deportation functions as both historical action and theological sign. The exile is punishment in the Deuteronomistic interpretation of history: covenant breach leads to exile. The chroniclers are clear about the cause-and-effect, even if they don’t narrate legal pleas or repentance sequences. You can see that connection threaded through the prophets too.

Jehoiachin in the prophetic texts: Jeremiah and Jeconiah’s curse

You’ll find Jeremiah’s voice sharp on Jehoiachin. In Jeremiah 22, the prophet speaks about kingship as moral stewardship and then directs a blistering admonition at the house of David. There’s a specific oracle against Jehoiachin (Jeconiah): a childlike image of a parent and child, a cruel reversal, and a curse on the line. See Jeremiah 22:24-30. The passage is raw: a king that people expect to sit on his father’s throne will be exiled, a man given to the gods who won’t possess the inheritance.

When you read Jeremiah, it’s hard to avoid feeling anger for both sides: the prophet’s righteous indignation and the king’s precariousness. Jeremiah’s words are part theological argument, part political prognosis. In that prophecy, Jehoiachin becomes a symbol of covenant failure; his fate is meant to dissuade others and to explain the catastrophe theologically.

This curse causes theological discomfort later. When you look at the New Testament, Jehoiachin appears in a lineage that seems at odds with Jeremiah’s declaration. More on that later when you consider Matthew’s genealogy.

Life in Babylon: from captive to forgotten king

If the deportation signals an end, it is not an absolute annihilation. Jehoiachin’s story in Babylon has a twist. You imagine him first in the dark: a king stripped of dignity, housed in a foreign court with other deportees, given a ration list and a new name. The biblical texts catalog the fate of his household and the “skilled workers” taken to Babylon, where they will be put to imperial use (2 Kings 24:14-16).

But somewhere between the chronicled humiliation and historical oblivion, a surprising flicker of mercy appears. Many years after the deportation, during the reign of Evil-merodach (Amel-Marduk), Jehoiachin is released from prison and treated honorably — assigned a regular allowance and given a seat of honor among the kings who were with the king of Babylon (2 Kings 25:27-30). You can almost feel the absurdity: a man who once wore Judah’s crown is now a pensioner in Nebuchadnezzar’s successor’s palace.

Jehoiachin’s release suggests a complex human reality obscure to the imperial narrative: mercy, political expediency, or changing dynastic rituals. Babylon might have wanted to cultivate goodwill among exiles or to rewrite the symbolic geography of power. Or maybe Evil-merodach simply showed a private kindness. Any way you slice it, the reversal complicates the earlier doom.

You can also corroborate this release in the parallel account in Jeremiah, which echoes the same narrative move: Jeremiah 52:31-34. The historiography doubles the point — Jehoiachin’s ending is not merely tragic in the sense of final ruin. There’s a note of survival, of grudging honor. That unravels the narrative binary you might have been expecting.

The genealogical knot: Jehoiachin and the line of the Messiah

You’ll be aware that theological debates knot around Jehoiachin because of Jeremiah’s curse and his place in the genealogy of Jesus in Matthew. Matthew lists Jehoiachin (as Jeconiah) in the lineage up to Joseph, the legal father of Jesus: see Matthew 1:11-12. That genealogy is a firm inclusion of Jehoiachin in Matthew’s legal-historical sweep.

If you’re theologically sensitive, you notice the tension: Jeremiah pronounces a curse on Jehoiachin’s line, but Matthew, apparently unconcerned, places Jehoiachin squarely in the line of David that culminates in Jesus. How do you reconcile the prophetic denunciation with the New Testament genealogy? Different interpreters approach this in different ways. Some argue that Jeremiah’s curse was conditional or that it was reversed implicitly by God’s larger redemptive plan. Others say Matthew is constructing a legal lineage — Joseph’s adoption of Jesus establishes legal claims to Davidic descent — and therefore Jesus’ legal, not biological, claim is emphasized, sidestepping the prophecy’s legal implications. You will find discussions of this knot throughout Christian tradition.

The inclusion forces you to think about biblical causality, divine promise, and how later authors repurpose earlier texts. It’s not just about Jehoiachin as a man; it’s about how memory and reinterpretation shape identity across centuries.

Theological and moral reflections you can take from the story

What are you meant to learn when you read Jehoiachin? Because the narrative resists a single moral, it invites many small, intimate reflections rather than an axiomatic conclusion. The exile narrative is both judgment and pedagogy. It is a warning about spiritual fidelity in covenant language and a realist account of political consequence.

First, you sense the fragility of leadership. Jehoiachin’s short reign is an index of political precarity. If you hold power, you’re always at risk of larger forces you cannot control. That humbling fact is not merely ancient; it speaks to modern leadership’s illusions of permanence.

Second, the story insists on communal consequence. Exile isn’t individualized punishment; entire households and communities suffer when national decisions go wrong. It challenges you to think about policy ethically — the decisions of rulers ripple outward in human terms.

Third, there’s mercy threaded into catastrophe. Jehoiachin’s release complicates the doctrine of retributive justice. The narrative suggests that even when consequences seem final, there is room for unexpected grace. That nuance refuses your desire for pure moral neatness.

Finally, you’re asked to notice how texts speak to each other across time. Jeremiah’s prophetic judgement and Matthew’s genealogy converse in ways that force theological creativity: do curses persist, or can covenantal promises reframe them? The Bible is not a single-voiced tract but a conversation between memory, law, prophecy, and later re-signification.

Literary considerations: what the biblical authors emphasize

Read the biblical accounts as literature and you’ll notice technique: compression, repetition, and selective emphasis. The Deuteronomistic historian is economical. The chronicler overlays certain theological interpretations. Jeremiah is poetic and prophetic — he uses striking imagery and rhetorical questions. Matthew, on the other hand, is deliberately constructing a legal and theological lineage.

In literary terms, the repetition of exile motifs — deportation, loss of land, removal of the elite — produces a kind of dirge. It’s an aesthetic built on absence. The writer doesn’t need to describe the daily humiliations in detail; the accumulation of concise statements about deportation does the work. You feel the weight of absence more than you read about it.

The narrative also uses names as symbolic devices. Jehoiachin’s alternate name, Jeconiah, has been the site of later commentary and symbolism. The lineage lists reuse names to make theological claims. The literary memory of a small king becomes a mechanism for larger theological claims about covenant, identity, and the continuity of David’s line.

Jehoiachin in post-biblical tradition

You could follow Jehoiachin beyond the biblical corpus into Jewish and Christian traditions. Rabbinic literature sometimes treats him sympathetically, focusing on the mercy shown to him in Babylon. Christian theological reflection tends to see him as an affirmation of God’s willingness to preserve a remnant and to keep the Davidic line alive despite curses and failures.

Historians and archaeologists add another layer: Babylonian records confirm deportations and practices of exile. When you look at the Babylonian Chronicles or administrative tablets, you catch glimpses of the imperial policy. The biblical text thus sits between external corroboration and theological reflection. That multiplies your interpretive responsibilities: you have to account for both historical reality and theological meaning.

Contemporary resonance: why his story still matters to you

There’s a reason this story feels modern. The experience of displacement, state violence, political marginalization, and the intimate humiliation of being uprooted are tragically contemporary. You can imagine a family leaving everything because a foreign power dictates their movements — the pain is not merely ancient.

Jehoiachin’s story also matters because of how the renegotiation of identity occurs after a catastrophe. The exiled community had to invent a future. That process of preserving memory, adapting rituals, and reinterpreting promises is exactly the situation of many displaced communities throughout history and your present moment.

The story also forces you into moral complexity. No single character is fully heroic or fully villainous. You are left with humans who make poor choices, suffer consequences, show mercy, and receive it. That is a more honest moral landscape than you might prefer, and it’s perhaps why the story endures: it looks like real life.

How you might read this text devotionally or historically

If you approach the text devotionally, you’ll find lament and hope. The exile narratives have given rise to some of the Bible’s most plaintive prayers. You’re invited to confess communal sin, to grieve loss, and to anticipate restoration. The reversal for Jehoiachin becomes a small picture of divine mercy that refuses to be reduced to simple law.

If you approach it historically and critically, you’re doing different work: tracing political motives, imperial logistics, and the mechanisms of exile. You might want to consult archaeological evidence, check Babylonian administrative records, or read contemporary scholars who parse the chronology and the demographic implications of the deportations.

Both approaches can coexist. You can read Jehoiachin’s life as a theological parable while also acknowledging the complicated realities of imperial policy. That double vision is, in itself, instructive about how texts work across genres.

What students of scripture often miss

One thing that students of scripture sometimes miss is the human texture in these brief accounts. Jehoiachin is not merely a cipher for doom. He is a young person whose life was redirected by geopolitical force. There’s also the social detail — the mention of craftsmen and smiths — that reveals the economic and cultural loss. The exile stole not only leaders but also the cultural capital that would have sustained the community.

Another point you might overlook is the multiplicity of voices within the Bible. Different books have different agendas. Jeremiah’s passion is prophetic righteousness; 2 Kings is historical theology; Chronicles reframes history for a returning community. When you notice these distinct signatures, the narrative makes more sense as a conversation, not a monologue.

Questions you can carry with you

When you finish the story, don’t be satisfied with tidy answers. Ask instead: What does it mean for God’s promises when a line is cursed in one prophet and reclaimed in the gospel? How does exile shape the self-understanding of a people and a religion? How do you read histories that mix theology and events without losing the nuance? These are not easy questions, and you won’t find simple answers, but they’re useful company when you read the text again.

You’ll also want to ask personal questions: how does power feel when you wield it, and how do you imagine its loss? How do communities preserve hope after displacement? Jehoiachin’s story invites you into these moral and existential inquiries without resolving them.

Final reflections

In the end, Jehoiachin is less interesting as an individual triumph or tragedy than as a node in a larger network of memory. His brief reign and deportation condense the historical and theological problems the Bible keeps returning to: covenant fidelity, imperial domination, broken kingship, and mercy after punishment. The surprise of his later release complicates your expectations and makes the story stubbornly human.

When you read 2 Kings 24:15, let the terse line sit with you. Ask what it would be to be taken from your home with those closest to you, hurled into a foreign court, and then, years later, be given a small dignity that cannot replace what was lost. That ambivalence — where grief and mercy coexist — is perhaps the deepest lesson of Jehoiachin’s life.

If you want to explore the primary texts further, start with these passages: 2 Kings 24:8-17, 2 Chronicles 36:9-10, Jeremiah 22:24-30, 2 Kings 25:27-30, and Matthew 1:11-12. These will let you see how different biblical authors tell the shape of the same life in different keys.

Explore More

For further reading and encouragement, check out these posts:

👉 7 Bible Verses About Faith in Hard Times

👉 Job’s Faith: What We Can Learn From His Trials

👉 How To Trust God When Everything Falls Apart

👉 Why God Allows Suffering – A Biblical Perspective

👉 Faith Over Fear: How To Stand Strong In Uncertain Seasons

👉 How To Encourage Someone Struggling With Their Faith

👉 5 Prayers for Strength When You’re Feeling Weak

📘 Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery – Grace and Mercy Over Judgement

A powerful retelling of John 8:1-11. This book brings to life the depth of forgiveness, mercy, and God’s unwavering love.

👉 Check it now on Amazon

As a ClickBank Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Acknowledgment: All Bible verses referenced in this article were accessed via Bible Gateway (or Bible Hub).

“Want to explore more? Check out our latest post on Why Jesus? and discover the life-changing truth of the Gospel!”