Jehoiakim: The King Who Burned Jeremiah’s Scroll (Jeremiah 36:23)

You probably know the broad strokes: a prophet speaks, a king refuses to listen, and somebody gets angry enough to burn a piece of paper. But the scene in Jeremiah 36 feels, when you look at it closely, like one of those domestic arguments that suddenly reveals everything about the people in the room — the power relationships, the small cruelties, the patterns of avoidance. You read it and you don’t just see a historical incident. You see a habit of the heart. You know what contempt for truth looks like in real time.

The episode in one line

Jeremiah dictated a written message from God; Baruch the scribe wrote it and read it publicly; officials took it to King Jehoiakim; the king cut the scroll with a penknife and threw it into the fire until it was consumed. You can read the whole narrative here: Jeremiah 36:1-32. The specific, almost obscene image — the knife cutting the scroll and the roll going into the flames — is in Jeremiah 36:23. The scene is brief. The implications are long.

Who was Jehoiakim?

When you’re trying to picture Jehoiakim, you can start with the political facts. He was the son of Josiah and became king at a time when Judah was squeezed between bigger powers. Egypt still had been a force, Babylon was rising, and the internal health of the nation was frail. Scripture gives you the immediate facts of his reign: “Jehoiakim was twenty-five years old when he became king, and he reigned eleven years in Jerusalem. He did evil in the eyes of the Lord, just as his predecessors had done.” Read that here: 2 Kings 23:36-37. The report is blunt and not especially interested in nuance; you get an official verdict: he did wrong.

You don’t get, from the biblical snapshots, a full psychological portrait. But you get choices. He was placed on the throne in turbulent circumstances and he chose pragmatism — and often violence — over repentance. That choice is precisely what brings him into conflict with Jeremiah.

The narrative in Jeremiah 36: the facts, again

The chapter reads like a short play. Jeremiah tells Baruch to write down everything he’s been preaching because the message keeps getting ignored when he says it aloud. Baruch composes the scroll; Jeremiah sends him to the temple, where it’s read aloud on a fast day to all who would listen. People are moved, the officials hear, and they report to the king. Jehoiakim summons the scroll, listens to parts of it, and then does the symbolic thing: he cuts it up and burns it. It’s all there in a single compressed arc: Jeremiah 36:1-32. The king’s gesture is immediate, public, and theatrical. That matters.

If you read the chapter and then stop — just stop — you’ll see how much that act holds. The scroll isn’t just a piece of paper. It’s a claim, a summons, an accusation couched in divine terms. Burning it is not neutral. It is an attempt to disqualify the whole enterprise of prophecy by consuming its physical medium.

The act of burning the scroll (Jeremiah 36:23)

The knife and the fire: “So the king ordered, and they took Baruch the scribe and Jeremiah the prophet, and they put them in the court of the guard. Then the king sat in the winter house in the ninth month, and there was a fire burning on the hearth before him. And whenever the king had read three or four columns, he cut it off with the penknife and threw it into the fire that was on the hearth until the whole scroll was in the fire that was on the hearth.” See the arresting, small details in Jeremiah 36:22-23. There is a domestic ordinariness to the scene — a hearth, a penknife — and that ordinariness is what makes it worse.

You should notice the rhythm: the king reads a chunk, makes a decision, cuts it out, and discards it. It’s a repetitive defiance. The action is not decisive in a single blow; it’s methodical. Each cut says: I will not be taught. I will not be held accountable. I will choose what remains. The scroll’s destruction is incremental, intimate, almost petty. That pettiness is precisely the point.

Baruch, the scribe you should notice

Baruch is crucial. He writes down words the people have been too comfortable to hear in spoken form. He reads them publicly, and for his trouble he’s dragged before the officials. He does the practical, vulnerable work of preserving the message when others won’t. The text records him as not merely an assistant but a partner in the prophetic project: remember that the scroll is not Jeremiah’s diary; it’s the result of a prophetic word formed into a publicly accessible object. You can read Baruch’s presence throughout Jeremiah 36: Jeremiah 36:4 and the subsequent verses that show him acting as the bearer and reader of the message.

What I think you notice, if you look for it, is how vulnerable the prophetic function is made by modes of communication. If words can be written, they can be read; if they can be read, they can be heard publicly; if they can be heard publicly, they can be judged — or destroyed. Baruch stands at the interface of speech and record, and that role is both heroic and dangerous.

Historical and political context: why the king was irritated

You don’t need a PhD to see the geopolitical tightrope Jehoiakim walked. In his day, Babylon under Nebuchadnezzar was flexing its muscle; Egypt still had influence; internal institutions in Judah were crumbling. Jeremiah’s message — that Babylon was God’s instrument of judgment — was theologically explosive and politically destabilizing. Jeremiah had been saying that submission or resistance to Babylon would have consequences beyond diplomatic realpolitik. You can track the geopolitical claims in a longer prophetic context, for instance, in Jeremiah 25:1-11, where Babylon’s role is spelled out.

Jehoiakim’s reaction is also a human one: he sees a threat to authority, to political survival, and chooses to neutralize the messenger. It’s the classic playbook: protect the throne, suppress the noise. But there’s also vanity and cowardice. Burning the scroll is power disguised as control.

Jehoiakim’s political choices and consequences

Jehoiakim’s reign is in many ways the prelude to catastrophe. The biblical narrative ties his refusal to repent and his misrule to the eventual devastation of Jerusalem and the exile. Later chapters make explicit the consequences of ignoring the prophetic warning; the Babylonians come, the temple is desecrated, and the monarchy is dismantled. The immediate political account of his reign — his years, his deeds, his folly — is recorded for you in 2 Kings 24:1-6. The text that follows the burning scene treats the act as less an isolated moment of petulance than as a representative symptom of systemic refusal.

You should consider that Jehoiakim’s attempt to silence prophecy did not silence God. That’s the narrative point. Baruch rewrites what was burned. Jeremiah is instructed to create another scroll with the same content plus a new word of judgment. The effort to destroy the message is recorded, preserved, and made to rebound — which is to say: the king’s inner compulsion to control truth ends up amplifying it.

Theological meaning: tearing up the envelope doesn’t stop the mail

There’s an important theological claim threaded through the episode: destroying a written form of God’s word doesn’t annul the word itself. You see this in the next verses, where Jeremiah tells Baruch to write another scroll containing all the words of the first one, along with additional prophecies of doom directed at Jehoiakim specifically. Read how the story continues in Jeremiah 36:27-32. The text carefully preserves the irony: the king burns the scroll to erase the word; God responds by making the word more durable.

For you, the lesson is not merely metaphysical. It is moral and practical: trying to obliterate moral truth by destroying its representations is not proof against the truth; it is testimony to your priority for comfort and control. The narrative makes moral stubbornness look pathetic, not tragic. That’s a sharp moral tilt.

The scroll as a symbol

Think about the scroll as more than physical parchment. It’s the covenantal indictment of the nation. Its destruction is symbolic — meant to erase the social and religious claim the scroll makes on the community. But the grand irony is that the scroll’s destruction becomes itself documented and preserved. It’s as if the world conspires to keep the very evidence the powerful try to abolish. The theological point is that you cannot expunge moral claims you disagree with by burning them; they will outlast your hearth.

Literary artistry: how the narrator shapes your judgment

There’s a craft to how the story is told. The author doesn’t need to editorialize loudly; the image of the knife slicing columns is enough to make you feel disdain for the king. The narrative moves you between the political and the domestic — a hearth, a penknife, officials coming in and out. The sensory detail gives the scene a lived quality that makes judgment almost inevitable. When you read it, you can’t help but see the contrast: prophetic word aiming for communal reorientation versus small, private acts of destruction.

The compression matters too. The event takes place in a brief sequence, which leaves you little time to rationalize Jehoiakim’s behaviour. It’s a kind of narrative judgment that uses economy to force your moral response.

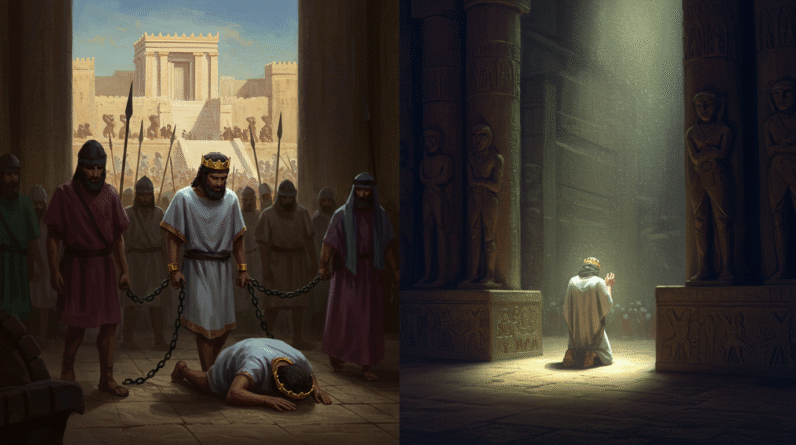

An ancient king, Jehoiakim, sat in a winter chamber beside a glowing hearth. He holds a small knife, slicing pieces of a prophetic scroll and tossing them into the flames. The parchment curls and burns while royal officials look on nervously. The scene is tense, dramatic, lit by firelight, with a sense of defiance and contempt. Historical realism, cinematic detail, warm fire contrasting with cold shadows.

Jehoiakim compared to other kings of Judah

If you read the biographies of Judah’s kings, you find patterns. Some kings are reformers. Josiah, Jehoiakim’s father, is a contrast: he reads and reforms, he renews the covenant, and dies in battle. You can read Josiah’s summary in 2 Kings 23:25. Under Josiah, the nation hears the Word and responds. Under Jehoiakim, the Word is burned.

You should see the story as part of a larger moral geography: a succession of choices by leaders that cumulatively shape the fate of a people. Kings like Hezekiah and Josiah are remembered for reform and for deferring judgment; kings like Jehoiakim are remembered for short-sighted policies and, in this case, symbolic rejection of covenant accountability.

The fate of Jehoiakim: a cautionary illustration

Scripture doesn’t let Jehoiakim’s act play out without consequence. There are prophetic words about his fate. Jeremiah announces judgment; other prophets echo it. You can read Jeremiah’s bleak pronouncement about Jehoiakim in Jeremiah 22:18-19, where he is likened to a dead body rejected from burial. 2 Kings tells you the political end: the Babylonians come, and Jehoiakim dies during the siege; he receives a dishonorable burial, which the text frames as fitting. See the political aftermath in 2 Kings 24:6. The story’s arc ties action to consequence in a way that leaves you unsettled if you’re tempted to admire the king’s boldness in the short term.

This is less about simplistic retribution and more about the rhythm of choices. Leaders who choose denial over accountability steer their nations toward collapse. The text reads that as moral causality rather than historical inevitability.

The resilience of prophetic speech

You should notice how many different forms of resilience show up in this story. Jeremiah’s speech resists oblivion by being written; Baruch’s obedience resists fear by bravely reading in public; the community’s willingness to listen resists indifference. But the deepest resilience the text asserts is theological: language about God’s justice and judgment may be paused, delayed, or violently interrupted, but it reappears. The second scroll is not merely repetition; it’s amplification. It contains not only the original indictment but a new, sharper address aimed at the king specifically. That’s recorded in Jeremiah 36:28-32.

You might think about the modern analogs: words banned, speeches suppressed, books burned. The story insists that suppression rarely eliminates truth; often, it gives the suppressed thing a bigger platform. That’s an uncomfortable lesson for any leader who favors suppression as a policy.

Censorship, power, and modern parallels

You almost can’t discuss a king burning a scroll without thinking of more recent history. From political book bannings to censorship of journalists, the dynamics repeat: someone with institutional power decides that certain speech is dangerous and acts to destroy it. The biblical story is older and tells the story without modern jargon, but the psychology is familiar: fear, shame, avoidance, and the wish to control the narrative.

If you read Jeremiah 36 as a parable for the present, you can ask yourself: where are you tempted to cut out inconvenient passages? When you delete a comment, ignore a complaint, or vilify a critic, you are doing small-scale versions of Jehoiakim’s act. The consequences are rarely as immediate as an empire falling, but they corrode trust and moral authority.

Moral lessons for personal life

This is not merely a political text. It’s also a moral mirror. When you choose comfort over correction, when you silence a friend because their honesty is uncomfortable, when you decide that your version of events should stand unchallenged, you reproduce the same pattern. The small domesticity of Jehoiakim’s act — the hearth, the knife — is meant to hit home. It suggests that villainy is often domestic and neat rather than spectacular.

So what do you do? You cultivate humility. You practice listening to people who challenge you. You preserve records of your commitments and then actually honor them. You don’t assume that the easiest version of yourself is the best one. Those are practical, quotidian responses to a heavy biblical lesson.

Baruch’s courage and the ethics of the scribe

We should return to Baruch for a moment. He is the figure who does the humble but costly work of transcription and public reading. He doesn’t wear prophetic titles in most descriptions; he is functional, a helper, a partner. But the story honors him by stressing his fidelity. When you think about prophetic ministry or moral truth-telling in your own circles, notice where the Baruchs are — the people who do the boring work that means you can’t claim ignorance later. They often bear disproportionate risk. Scripture gives them a kind of quiet sainthood.

Read the way Baruch acts in Jeremiah 36:4-10. He goes where the truth needs to go. He reads aloud in public. For that, he is threatened. But he persists.

How the episode shapes Jeremiah’s book

If you look at the book of Jeremiah as a whole, this chapter performs a function beyond its immediate narrative: it demonstrates and dramatizes the opposition the prophet faces, it anchors themes of endurance and the written word, and it gives a moral exemplum of how a people’s leadership can respond to prophetic warning. Without this episode, Jeremiah’s prophetic vocation could read like a string of private laments. With it, you see a public clash, an emblematic event that suspends the larger themes of judgment and fidelity in a vivid scene. It makes the abstract concrete.

The book thus becomes not only a collection of oracles but a record of conflict between prophetic truth and political defensiveness. That is what gives Jeremiah his dramatic energy.

Literary images: fire, knife, scroll

You can trace the symbolic weight of each object in the scene. Fire is a purifier and a destroyer; in prophetic literature, it often marks judgment. A penknife is intimate and small, almost ridiculous, used against a scroll of theological import. The scroll is a repository of memory and law. Each image says something: the king is using intimate tools to perform grand deletions; the violent action is petty; the means underscore the moral smallness. The narrator arranges these images to make you feel the contempt without stating it outright. Good writing does that: it shows you the thing so clearly that your judgment follows.

Scholarly observations you can savor

Scholars note several layers of interest: the chapter is an example of how prophetic materials were edited and preserved in written form, it shows the intersection of orality and literacy in the ancient world, and it demonstrates the social dynamics of public reading in the temple. You may find more technical reflections in commentaries and background studies, but the core is straightforward: written prophecy mattered, and power tried to control it. For your convenience, you can read the parliamentary episode in the canonical text here: Jeremiah 36:1-32.

What scholars emphasize — and you should notice — is that the episode is not an accusation against literacy or political authority per se, but against the abuse of authority that seeks to erase ethical demand. The surviving scrolls of Jeremiah suggest that the community eventually took pains to preserve the prophetic voice, precisely because they recognized how easily power could try to erase it.

How to read this if you’re leading

If you are in a position of leadership, this story is a warning about reflexive defensiveness. Leaders are tempted to think that controlling the narrative is identical to exercising power wisely. The text shows you the spiritual and moral cost of that confusion. You don’t gain legitimacy by muting dissent; you forfeit moral credibility. The narrative invites leaders to prefer truth-telling and listen to inconvenient voices.

In practical terms: make room for accurate record-keeping, welcome a range of perspectives, and avoid symbolic gestures that silence rather than address critique. If you have decisions to make and you protect them by marginalizing opposing views, you are acting like Jehoiakim.

The spiritual angle: repentance and refusal

The tension between repentance and refusal runs through Jeremiah. Jehoiakim’s act is one of refusal: not merely of a particular message but of the moral posture that would allow for change. Prophecy in Jeremiah calls for a heart willing to be reformed. The king’s burning of the scroll shows you what happens when that posture is missing: when the will is calibrated to self-preservation, you become incapable of moral listening.

If you take the story to your own spiritual life, ask where you truncate truth to avoid discomfort. The repentance asked in Jeremiah is not theatrical; it’s a slow, stubborn recalibration of desire. Jehoiakim refuses that recalibration. His symbolic illiteracy is a moral failure.

What the story invites you to do now

The ancient scene asks you to perform a small practical discipline: preserve difficult words. Keep a journal. Invite honest friends to name what they see. Read the records of your choices and make yourself accountable for them. The story of a burned scroll becomes a parable for the small moral architectures of your life: wills are drafted, commitments are written, and then you either honor or destroy your own records.

Another practical invitation: when you hear a difficult word, resist the urge to cut it out. Sit with it. Test it. If it is true, it will shape you in ways you can live with. If it is false, it will be unmasked by time and conversation. You are not required to accept every accusation immediately, but you should cultivate the habit of listening before you destroy.

Final reflections: the smallness that ruins

You finish this chapter feeling the sting of Jehoiakim’s pettiness. It’s not grand tyranny that makes him contemptible; it’s the tiny domestic gestures that add up: a hearth, a penknife, the small, slow decisions to cut and discard. The prophetic response — to write again, to persist — looks nobler because it is patient and generative. The book preserves that patient persistence as the moral answer to the king’s impatience and destruction.

When you leave this story, don’t simply file it under “ancient history.” Remember it next time you are tempted to tidy away an awkward truth, to delete a comment rather than engage, to silence someone who challenges your view. The smallness of those choices matters. They have moral consequences that go beyond the moment.

If this sketch of Jehoiakim — the king who burned Jeremiah’s scroll — has made you think about your own small acts of destruction, then the story has done its job. You’ve seen how public events and private decisions knit together, how the aesthetics of an action can reveal the ethics behind it, and how the power to burn a message is almost always an attempt to keep one’s conscience at bay.

If you want to reread the core scenes, the primary passages are here: Jeremiah 36:1-32, and the specific act is recorded at Jeremiah 36:23. For context on Jehoiakim’s reign and fate, see 2 Kings 23:36-37, 2 Kings 24:1-6, and Jeremiah’s condemnation in Jeremiah 22:18-19. For Baruch’s role and the continuation of the message, read Jeremiah 36:27-32.

Explore More

For further reading and encouragement, check out these posts:

👉 7 Bible Verses About Faith in Hard Times

👉 Job’s Faith: What We Can Learn From His Trials

👉 How To Trust God When Everything Falls Apart

👉 Why God Allows Suffering – A Biblical Perspective

👉 Faith Over Fear: How To Stand Strong In Uncertain Seasons

👉 How To Encourage Someone Struggling With Their Faith

👉 5 Prayers for Strength When You’re Feeling Weak

📘 Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery – Grace and Mercy Over Judgement

A powerful retelling of John 8:1-11. This book brings to life the depth of forgiveness, mercy, and God’s unwavering love.

👉 Check it now on Amazon

As a ClickBank Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Acknowledgment: All Bible verses referenced in this article were accessed via Bible Gateway (or Bible Hub).

“Want to explore more? Check out our latest post on Why Jesus? and discover the life-changing truth of the Gospel!”