Zedekiah: The Last King Who Saw Jerusalem Fall (2 Kings 25:7)

You probably know the scene before you read the verse: a king brought out trembling into the public square, his sons slaughtered at his feet, his eyes put out, and then he’s taken to Babylon to die in chains. That’s the blunt, almost cinematic end described in 2 Kings 25:7. But if you live with that moment a little longer, you can feel how it sits within decades of choices, pressures, political maneuvers, and prophetic warnings. This is not only a historical account; it’s an intimate study in how a person — a leader, a father, a human — can be undone by indecision and fear. You read this and, if you’re honest, you see how small human will is when history pushes back.

Why Zedekiah matters to you now

The story of Zedekiah is ancient, but it lands in your life because it asks what you do when everything you hoped would save you is failing. If you’re a leader of anything — a family, a company, a small group of friends — you’ll recognize the pressure: promises to keep, enemies at the door, advisors who whisper opposite things. Zedekiah’s fall isn’t simply political; it’s moral and personal. In reading about his end in 2 Kings 25:7, you’re nudged into asking whether loyalty to power or loyalty to truth will define your acts when the siege comes.

The late monarchy of Judah: a quick landscape

If you want the immediate context for Zedekiah, you have to see Judah as exhausted and squeezed. The Assyrian world order has collapsed; Egypt flirts with influence; Babylon stands at the center of raw ambition. Kings come and go with shorter and shorter reigns, and the people are pushed into compromises that feel like betrayals. The political climate is such that occupying powers install kings who will serve their interests — and your sense of autonomy erodes little by little. That’s the world Zedekiah steps into when he becomes king after Nebuchadnezzar deports Jehoiachin. See how the hand of empires rearranges houses, including your house, in 2 Kings 24:17 and 2 Kings 24:18.

Nebuchadnezzar and the imposition of a puppet king

You should picture Nebuchadnezzar standing offstage, not because he’s gentle but because his actions set the stage. After deporting much of the elite, he places Zedekiah on Judah’s throne as if rearranging chess pieces. The move looks pragmatic: install someone obedient, maybe malleable, who will keep peace and pay tribute. It’s recorded that Nebuchadnezzar appointed Zedekiah to rule 2 Kings 24:17-18. There’s a quiet tragedy in being chosen by an occupying power; you’re respected enough to be king but not respected enough to be trusted. You’ll sense the tension: is Zedekiah grateful, resentful, calculating, or panicked? All of it, probably, and mixed.

Zedekiah’s appointment and the early years

When you look at a man raised to the throne by a foreign invader, you should expect ambiguity in how he rules. Zedekiah is described as the son of Josiah’s son, a royal, and he ruled for eleven years in Jerusalem. On paper, it looks fine; in practic,e he inherits a state exhausted by tributes, weakened institutions, and prophetic criticism that has become sharper than before. The chronicler notes his reign in 2 Kings 24:18-20, and you can see the setup: the king is both figurehead and scapegoat, which is a dangerous combination. You begin to recognize that his choices will always be framed by what others — Babylon, Egypt, the prophets — demand of him.

The pressure of conflicting loyalties

If you were Zedekiah, every choice would be weighed in the kind of nervous calculations that keep you awake at night. Babylon demands loyalty; Egypt offers an alternative alliance; Jerusalem’s priests and prophet-sentinels demand religious fidelity. Zedekiah’s reign shows how impossible it is to answer all those claims. He rebels against Babylon eventually, a move that sounds bold on paper but is often impulsive or pressured by those around him. You can trace that rebellion in the narrative where his leadership visibly deteriorates as the city tightens under siege (2 Kings 25:1–3). It’s often not that he chooses one loyalty, but that he tries to split the difference until the seams give.

Jeremiah and the prophet’s gaze

You can’t read about Zedekiah without meeting Jeremiah, who is the voice that refuses to flatter. Jeremiah is not a comfortable adviser; he is relentless in naming the costs of false hope. When Zedekiah consults Jeremiah, he hears a message that cuts to the possibility of surrender as a moral necessity. For example, Jeremiah’s interactions with the king during the siege are dramatic: he forewarns, advises surrender, and remains faithful to speaking unpopular truth. See part of that exchange where Jeremiah speaks plainly and is brought before the king in Jeremiah 37:17 and again in Jeremiah 38:14. You sense how the prophet’s insistence is almost an act of care, which makes it more unbearable when the king ignores him.

The cruelty of political expediency

The court’s reaction to Jeremiah shows how political expediency can become cruel quickly. Officials feel threatened by his words, and you watch as their fear transforms into violence against a man who, at worst, is telling uncomfortable truths. Jeremiah is thrown into a cistern and left to die, only to be rescued later when the king intervenes. You can trace the emotional thread in Jeremiah 38:6–13, which shows how easily fear silences conscience. The story forces you to ask: when you are afraid, how do you treat those who challenge you? Do you send them away or listen?

The siege, the breakout, and the capture

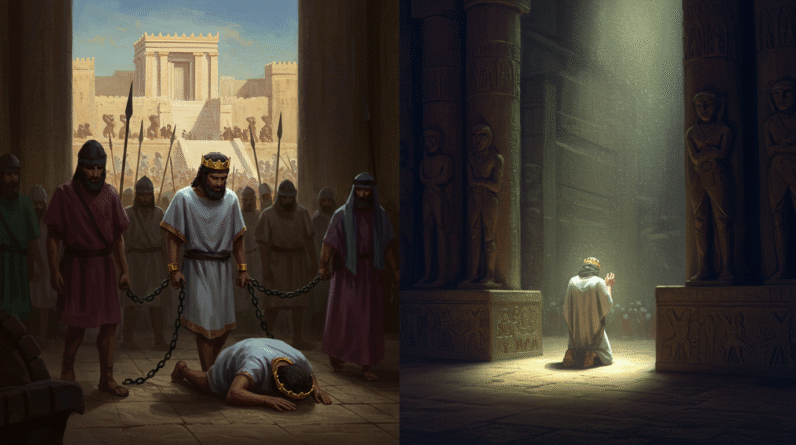

You now come to the siege’s second act, which is both militarily decisive and personally catastrophic. Jerusalem is surrounded; food runs out; morale collapses. Zedekiah’s city endures famine and exposure, and then he tries to escape. The attempt is almost farcical in a tragic way: the king slips out at night with a handful of followers and attempts to cross the Jordan, perhaps imagining a narrow corridor of safety. But the effort fails, and the Babylonians seize him in the plains of Jericho. The narrative in 2 Kings 25:4–7 is clinical: they capture him, present him to the captain at Riblah, and his sons are killed before his eyes. You are meant to feel the embarrassment and the humiliation as if they’re almost theatrical, and you understand that the punishment is designed to strip him of dignity first and personhood later.

The execution of his sons and the blinding

When you read 2 Kings 25:7, it hits like a moral puncture. The order to slay his sons and then put out his eyes is both a physical and symbolic erasure: his line is cut off, his capacity to see — to judge, to plan, to hope—is removed, and his kingship ends in darkness. This is a cruel, calculated message from Nebuchadnezzar to any would-be rebel: you will be rendered powerless and made an object of pity. The passage is short and objective; that objectivity is what makes it feel colder. You sense, too, the personal void such violence creates in the surviving human: a father who must watch his children die before his senses are taken from him. The cruelty is as performative as it is punitive.

Parallels and double-checks: Jeremiah and 2 Kings

If you like corroboration, the letters and narratives overlap. Jeremiah’s book records the moment with a slightly different emphasis, especially in how it records Zedekiah’s attempts to hide from the prophet and prophecy. The capture and the aftermath are reiterated in Jeremiah 39:5–7 and a later summary in Jeremiah 52:10–11. You see the incident from multiple angles: historical narration, prophetic lament, and later summarizing reflection. Each recounting adds a layer — legal, moral, theological — and you get a more complete picture when you read them together. It’s like having different witnesses describe the same accident: no two accounts are identical, but together they shape the truth.

Ezekiel’s note and the fate of the remnant

Ezekiel also picks up the story, but not to recount the gruesome details. Instead, Ezekiel frames what happens as part of God’s larger dealings with a nation that has failed in covenant. He speaks about dispersal and exile with imagery of displacement and loss, and you can see his view in Ezekiel 12:13. This is significant because the exile is not just political; in prophetic literature, it represents spiritual catastrophe and also, paradoxically, a place where restoration might begin. You are therefore pushed to think about exile not only as punishment but as a phase where identity is remade.

What does Zedekiah teach you about leadership?

If you lead anything, you can extract lessons from Zedekiah that sting. First: indecision is its own vice. When you waffle between alliances, you surrender authority. Second: surround yourself with people who will tell you truth even when it hurts; otherwise, you’ll get the polished lies that make defeat more humiliating. Third: remember that moral courage sometimes means choosing the less flattering and more honest path, even if it looks like surrender. Jeremiah’s counsel offered an option that might have reduced suffering; Zedekiah’s fear led him elsewhere. When you think of leadership as image management, you end up making choices that are about saving appearances and losing everything else.

The cost of listening to the wrong voices

You should note how often Zedekiah listens to flatterers and military counsel instead of the prophetic voice that demands repentance or surrender. The court whispers of possible alliances with Egypt, and that quartered hope is what pushes him into rebellion. You can see the missteps in 2 Kings 24:20 and subsequent passages, where political calculus replaces moral clarity. The consequence is loss — not only of territory but of legacy and family. If you want to avoid that kind of loss, be wary of voices that only tell you what you want to hear.

The moral ambiguity of compromise

It would be too neat to make Zedekiah a simple villain. He is complicated — human enough that you sometimes sympathize. He is young earlier, uncertain, perhaps trying to balance impossible claims. When Babylon is the stronger, maybe resistance feels like betrayal of previous generations; conversely, submission may feel like a loss of dignity. You have to live with this ambiguity: sometimes compromise saves lives, sometimes it sells principles. The biblical accounts don’t present Zedekiah with saintly clarity; instead, they show a man muddled in fear and vacillation. That’s the thing that makes his story, in the end, tragically human.

When surrender is faithfulness

There are times when surrender is exactly the faithful choice. Jeremiah argues this point: surrender could have preserved more lives and left the community intact enough to rebuild. The prophet’s paradox is that obedience to God’s word often requires what looks like defeat. If you read Jeremiah 38:17-18, you see Jeremiah laying out the consequences honestly: follow God’s counsel and you may live. Zedekiah’s refusal becomes, then, not only a political misstep but a spiritual failure to submit to a difficult truth.

The personal tragedy: father, not king

When the account says his sons were killed before his eyes, it forces you to feel the intimate cruelty of political revenge. The act strips Zedekiah of roles he might have valued most — fatherhood, lineal continuity — and leaves him with a blind, hollow existence. You have to imagine the inner collapse of a man who was once king, now rendered impotent in both body and status. The narrative invites pity, and perhaps, if you allow it, the uncomfortable recognition that leaders are often people whose private sufferings are used as public warnings. That doesn’t absolve them, but it humanizes the cost.

Blindness as metaphor and literal consequence

The removal of Zedekiah’s eyes is a literal punishment and a metaphorical end. Without sight, he cannot plan; without heirs, his dynasty ends. He is physically and symbolically removed from the narrative of kingship. You should notice how the Bible sometimes uses physical actions to underline theological points: the blind king is both a tragic victim and a symbol of failed vision — not seeing God’s will, or not seeing the consequences of his acts. 2 Kings 25:7 and Jeremiah 39:7 make this plain.

The exile and the small, slow return

You’ll notice that the end of Zedekiah’s reign marks a broader end: the temple’s destruction, the elites’ deportation, and the scattering of community life. Yet the biblical story doesn’t end with total annihilation. Later, small remnant returns, and the complex work of reconstitution begins. The exile becomes the stage for theological reflection, lament, and eventually renewal. Think of it as a trauma that compels a community to rehearse its identity differently. Ezekiel and others imagine a restoration that is both spiritual and communal, and that future-oriented faith arises out of the ashes of the old order. You can read about the capture and deportation sequence in 2 Kings 25:8-12.

How communities survive catastrophe

When you look at Judah after Zedekiah, the ways communities survive are complex: some adapt by blending into new cultures, others by holding tightly to traditions. Prophetic literature often frames survival as a test that strips away illusions and forces fidelity. If you’re part of any group changing, you can see similar dynamics: the temptation to nostalgia, the impulse to scapegoat, and the necessity to adapt. The biblical writers insist that survival is not merely biological but moral and spiritual — that how you respond to catastrophe defines what you become.

Reading Zedekiah in your life: practical, spiritual advice

If you want to draw concrete lessons from Zedekiah, start with this: decide who will be your Jeremiah. You need someone who will name the hard truth even when it’s unpleasant. Cultivate that honesty in your councils and resist the flattering yes-men who smooth every crisis. Second, scrutinize your loyalties: are you binding yourself to a powerful partner because you fear loneliness more than you fear compromise? Third, understand that courage sometimes looks like capitulation; the heroic choice may be to stop the damage rather than to maintain a tarnished honor.

Don’t romanticize tragic leadership

You might be tempted to romanticize Zedekiah — to make him a noble, tragic figure who resisted the empire. That’s attractive because it allows you to imagine yourself as heroic in defeat. But the biblical verdict complicates that. Zedekiah’s resistance brought more harm than good, and the prophets insist that righteous surrender would have been better. If you’re sincere about moral action, don’t confuse self-image with virtue. Let the story teach you the difference between grand gestures and responsible action.

A final reading: grief, responsibility, and the ambiguity of punishment

You end with an odd mixture of grief and moral clarity. Zedekiah’s story is not a simple morality play; it’s a meditation on how people behave when trapped between bigger forces. You are left grieving for the families lost, the city destroyed, and the ways leaders can fail those who depend on them. Yet the narrative also insists on responsibility — leaders’ choices have consequences. The biblical account is not vindictive in a cheap way; it is trying to teach you how to live in a world where power is real and where faithfulness often requires painful humility.

How to hold both judgment and sympathy

If you’re one of those people who want to pass quick judgments, Zedekiah’s story frustrates you. The text refuses simple condemnation or complete sympathy. It wants you to hold both: understand his fear, yes, and measure it against the cost of his choices. That balanced posture is hard but necessary. If you cultivate it, you’ll probably make fewer catastrophic choices yourself.

Closing thoughts

When you close the Bible after reading 2 Kings 25:7, you might be tempted to move on to less harrowing chapters. Don’t. Let the image of Zedekiah — blind, led into captivity after his sons were killed — sit with you a little while. Let it be a caution that leadership without courage and counsel is hollow. Let it be a warning that sometimes the bravest thing you can do is the unpopular thing that saves lives. And let it be a reminder that history often writes the end for those who cannot see the future clearly.

If you want to read the key passages I quoted in this article, here they are again for reference:

- 2 Kings 25:7

- 2 Kings 24:17

- 2 Kings 24:18

- 2 Kings 25:1

- 2 Kings 25:4–7

- 2 Kings 25:8–12

- Jeremiah 37:17

- Jeremiah 38:14

- Jeremiah 38:17–18

- Jeremiah 39:5–7

- Jeremiah 52:10–11

- Ezekiel 12:13

Explore More

For further reading and encouragement, check out these posts:

👉 7 Bible Verses About Faith in Hard Times

👉 Job’s Faith: What We Can Learn From His Trials

👉 How To Trust God When Everything Falls Apart

👉 Why God Allows Suffering – A Biblical Perspective

👉 Faith Over Fear: How To Stand Strong In Uncertain Seasons

👉 How To Encourage Someone Struggling With Their Faith

👉 5 Prayers for Strength When You’re Feeling Weak

📘 Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery – Grace and Mercy Over Judgement

A powerful retelling of John 8:1-11. This book brings to life the depth of forgiveness, mercy, and God’s unwavering love.

👉 Check it now on Amazon

As a ClickBank Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Acknowledgment: All Bible verses referenced in this article were accessed via Bible Gateway (or Bible Hub).

“Want to explore more? Check out our latest post on Why Jesus? and discover the life-changing truth of the Gospel!”