Jehoahaz (Shallum): The King Who Reigned For Only Three Months (2 Kings 23:31)

You come to this story because the shortness of it arrests you. There’s something about a reign that lasts three months that feels like a deliberate misstep in the narrative of kings and kingdoms — as if time itself turned away. Jehoahaz, also called Shallum, appears in the royal lists almost as a punctuation mark: brief, almost accidental. The Bible tells this with a simplicity you can’t ignore: 2 Kings 23:31 — “Jehoahaz was twenty-three years old when he became king, and he reigned in Jerusalem for three months. The king of Egypt deposed him at Jerusalem and put him in chains in Egypt.” You read it, and something about the economy of those words lodges in your throat.

If you’re used to stories of long rule, wise reformers or tyrants who last, this one is a strange interlude. If you’re tracking patterns, you might want to know: why did this happen? What should you make of a king whose entire career could fit into a single season? If you’re looking for lessons, you’ll find them, but they’re not packaged with morals. They come as quiet implications: about power, contingency, and the way larger forces shape small lives.

The immediate context: Josiah’s last campaign and the vacuum he left

Before Shallum’s brief rule, there was Josiah, a king who had become a kind of hinge in Judah’s history. He had led reforms and tried, in a way you almost admire, to wrest the kingdom’s life back from entrenched idolatry. The narrative turns suddenly in the account of Josiah’s death. He confronts Pharaoh Neco of Egypt at Megiddo and, against advice, meets him in battle and is mortally wounded. The chronicler’s voice is almost chaotic in that episode; you can hear the abruptness of an arc broken. See how the text places Josiah’s end: 2 Kings 23:29 and the fuller account in Chronicles: 2 Chronicles 35:20-24. Josiah dies; Judah’s leadership is suddenly exposed.

You can imagine the court: shock, mourning, the scramble for succession. In political life, when a strong personality falls, smaller, less durable figures appear almost by design — placeholders at the mercy of those who hold military and economic power. Jehoahaz is one such figure. He inherits not only a kingdom but the consequences of a foreign military presence that can rearrange kings at will.

Who was Jehoahaz (Shallum)?

He is introduced thinly, as if the writer has no patience for biography. 2 Kings 23:31 tells you his age — twenty-three — and the bare facts of his rule and deposition. You learn his two names in different registers: Shallum, his given name; Jehoahaz, a name that ties him to the divine “Yah” (Jeho-), insinuating that his kingship is, in some theological sense, under God’s name. Names mean more in this world than they sometimes do for you and me: they’re political claims as much as familial markers.

In 2 Chronicles 36:1-4, you get the parallel record, which underscores his brevity and subsequent fate: put in chains in Egypt. The chronicler is almost irritated by the uselessness of this king: he’s listed, he’s removed, and the story moves on. You feel the dryness of the archive — people reduced to entries. But that dryness itself makes the human outline sharper. Three months: you can imagine how quickly the courtiers stop pretending to forward his decrees. You can imagine friends who hedge their loyalties within a week.

The power beyond Judah: Pharaoh Neco and imperial rearrangement

To understand Jehoahaz’s three months, you have to look outside Judah. You have to look at Egypt and the politics of the ancient Near East. Pharaoh Neco — historical Neco II — was on the move, concerned with contests over Assyrian and Babylonian spheres of influence, and Josiah’s confrontation with him had consequences for Judah’s sovereignty. The Bible records that Neco deposed Jehoahaz because he preferred another candidate, Eliakim, whom he renamed Jehoiakim. Read the sequence in 2 Kings 23:33-34, which explains the overthrow, the renaming, and the imposition of tribute: a hundred talents of silver and a talent of gold.

This is imperial politics in its bluntest form. You see the logic: a foreign ruler installs a pliant local king who will pay and who will not challenge his plans. Jehoahaz, despite his dynastic claim, is removed because he is not the man Neco needs. This is also why the brevity of the reign feels less like an anomaly and more like a consequence. When larger armies move, smaller kings are sometimes moved as objects are moved on a board.

The three months in detail: what the text actually says

The biblical account insists on the facts without ornament. 2 Kings 23:31-34 gives you the arc: proclamation, three months, deposition, exile. It is efficient. You don’t get a catalogue of his policies, because there were no significant policies to record. The chronicler in 2 Chronicles 36:2-4 frames it in terms of legitimacy and constraint — more judge than storyteller — emphasizing the chains and the Egyptian custody.

If you trace these verses slowly, even the economy of language is instructive. Notice how quickly the narrative’s attention abandons Jehoahaz. He is useful for the succession’s logic — to show who follows whom — and then he falls out of the story. The text’s neglect is a kind of judgment, but also a historical note: he left no initiatives, no reforms, no counterfactual legacies. His kingship is mostly a hinge through which the next king is set.

Eliakim, Jehoiakim, and the substitution of rulers

What happens after Jehoahaz is almost as telling as his deposition. Pharaoh Neco doesn’t just remove a king; he imposes another in his place. Eliakim becomes Jehoiakim, and his very name is altered to signal political subordination. This is in 2 Kings 23:34 and echoed in 2 Chronicles 36:3. The renaming is more than cosmetic: it’s a rebranding for diplomatic compliance.

You should notice how tribute functions here. The imposition of a hundred talents of silver and a talent of gold is explicit in 2 Kings 23:34. This is not merely a tax; it’s a political statement: you are paying for the privilege of owing. When you read that, you can imagine the palace ostentatiously stripped of its treasures, administrators dispatching chests, families counting what remains. The economics of vassalage is not abstract; it’s an everyday constraint.

Why this story matters: themes you can take into a small life

Jehoahaz’s reign is brief, but the story holds lessons about contingency. There’s a knowledge here that if your life is ruled by larger structures — empires, markets, systems — your plans can be overturned by decisions far from you. You might be someone who invests in long-term intentions, only to find an unforeseen policy or a market collapse making them impossible. The biblical narrative gives that sense not as a moral about luck but as a sober mapping of how human lives are embedded in power.

Another theme is the fragility of authority that lacks capacity. If kingship is measured not by right but by enforcement, then legitimacy is precarious. Jehoahaz had a dynastic claim; Neco had soldiers. You can see this in your own life: claims of righteousness or moral authority can be face-to-face with sheer force, and often force, whatever its justice, wins. The text doesn’t moralize this so much as show it.

There’s also the matter of being forgotten. Jehoahaz’s omission from narrative attention is a kind of erasure. You can imagine what that does to the friends and family left behind. Human lives are precariously recorded; the archive is selective. When you think about your own footprint — the emails you’ll leave unread, the messages that will be lost — there’s a melancholic solidarity with Jehoahaz.

The theological twitch: what does God have to do with this?

The biblical writers are not uninterested in theology here, but they are restrained. The Deuteronomistic historian — the editor who frames kings’ stories — often compresses moral evaluation into the facts of the reign: obedience equals flourishing, disobedience equals collapse. With Jehoahaz, the evaluator is minimal: his short reign and deposition are simply recorded. You might read that as an implicit moral: if a ruler doesn’t align with God’s will, he won’t be remembered. But the text does not say that explicitly for Jehoahaz.

Instead, you get an indirect theology: God’s sovereignty can accommodate human instruments and foreign might. Even a king with the name Jehoahaz — whose title invokes God — can be moved by Pharaoh’s will. There’s a sort of theological humility here: God’s governance doesn’t always override human political agency in dramatic rescue. Sometimes God’s story is made through the small arithmetic of armies, alliances, and bribes.

This thought can be uncomfortable. If you were hoping for immediate divine vindication for every wrong, this story resists that hope. It offers a more complicated faith: one that insists on divine presence but permits human contingency. You can hold both things at once, even if it leaves you uneasy.

The human detail: chains, exile, and the psychological image

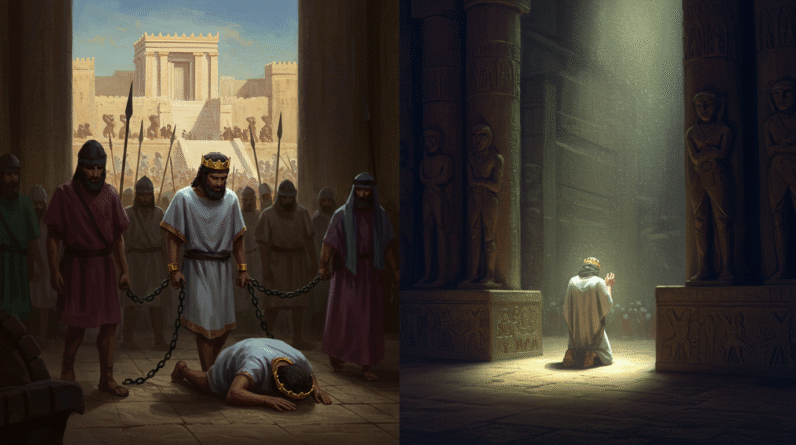

The image of Jehoahaz in chains in Egypt is striking. 2 Kings 23:33 and 2 Chronicles 36:4 tell you that he was put in bonds; the language is stark. You should imagine the humiliation: a king who once sat on a throne, receiving delegations, is escorted like a criminal to a foreign land.

There are smaller, human speculations you can make here that the Bible doesn’t narrate, but that feel true. Perhaps there was a brief moment where Jehoahaz expected to rule longer. Maybe he had a plan — to secure a marriage alliance, to reform a certain priesthood, to reopen trade routes. All of those plans evaporated. You can feel an echo of that in your own disappointments: the plans you had at twenty-three that are undone by someone else’s mandate. The text’s economy leaves room for your empathy; you can fill those gaps with your sense of what it means to lose possibility.

Historical layers: archaeology and imperial context

If you care about what happened beyond the scriptural account, you can place Jehoahaz in the well-documented sweep of Near Eastern politics. Pharaoh Neco is recognizable in other ancient sources as a ruler moving to secure routes and alliances at the end of the Assyrian order and the rise of Babylon. His involvement in Carchemish and the politics of the region shows why Judah, a small kingdom, had little to say about its own fate.

The biblical text is part of a broader archival world: inscriptions, annals, and later historians sketch the outlines of these power moves. When you read the Bible alongside that evidence, it becomes less an allegory and more a narrow window into the messy mechanics of empire. That said, the text’s theological economy — the way it renders kingship and judgment — remains central to you if you’re reading for moral and spiritual insight. You don’t have to choose between history and theology; they can coexist, uncomfortable and revealing.

What Jehoahaz’s story doesn’t tell you — and why that omission matters

The story’s brevity is its defining feature, and what it doesn’t say is almost as loud as what it does. There’s no record of his policies, no prophetic confrontation, no moral exemplum applied to him in the way the text assesses other kings. The Bible is selective; it edits. You might feel annoyed at that selectivity, because you want the fuller portrait. But that very omission reveals something: some lives make no long-term dent in institutional memory, and the record itself is interested in patterns rather than every human life.

You might interpret that absence as cruelty, or simply as realism. It can be useful to hold both reactions. There is a justice to wanting every life told fully, and there is a narrative interest the chronicler protects: meaning, patterns, theological lessons. For your own life, that dilemma is familiar. Some of your days will be chronicled by others; many won’t. You can decide what that makes you: do you seek legacy at any cost, or do you accept living for smaller intimacies?

Jehoahaz in relation to the prophets and later memory

Jehoahaz hardly features in prophetic speeches. But his removal paved the way for Jehoiakim, who does figure in prophetic denunciations later in the text. The point is not to dwell on Jehoahaz as a figure of prophetic censure but to see him as part of a chain of leadership that culminated in political choices affecting Judah’s fate. If you’re tracing moral lines, Jehoahaz is a hinge you can scarcely hold; the greater moral discourse targets those who linger longer, whose decisions materially shape social and religious life.

There’s a subtle thing to notice: the prophets often speak to realities that persist beyond any single king’s moment. Jehoahaz’s three months appear as a minor turn, but the problems the prophets lecture — injustice, idolatry, reliance on foreign powers — are structural. So Jehoahaz’s story is not an exception to prophetic teaching but one small case in a larger pattern the prophets assume.

Reading the narrative like a person, not like an expert

You can read Jehoahaz’s short reign and still take it personally. Perhaps you are someone who looks for meaning in absences: the friend who doesn’t call back, the job that lasts three months, the romance that ends in a single season. In each case, the pattern is similar: presence is ephemeral, and authority can be arbitrarily revoked. The biblical episode makes that existential point without melodrama.

If you allow yourself to linger on details — the young king’s age, the chains in a foreign land — the story becomes intimate. History can be about human smallness as much as greatness. That’s not a depressing lesson so much as a clarifying one: you don’t need to be mighty to be instructive. Jehoahaz teaches you about contingency and the structural forces that shape lives, even when those lives have royal trappings.

Practical reflections: what you can take away

If you like takeaways, they are gentle and not fully consolatory. First: cultivate humility about control. Often, you are not the chief architect of outcomes; you operate within systems you cannot redirect with a single decision. Second: learn to mourn truncated projects. Jehoahaz’s loss invites you to practice grief for plans that vanish. That grief is a kind of gratitude for what could have been. Third: hold empathy for people erased by archives — in your own life, be the one who remembers others, who tells the smaller stories.

These aren’t strategies for political success. They are ways to orient yourself ethically and emotionally toward the world. Jehoahaz’s story isn’t a manual; it’s a whisper about how the world sometimes unfolds when the small meets the large.

If you want to read the primary texts

If you decide to look directly at the passages, start here and read slowly. Let the economy of the narrative sink in.

- 2 Kings 23:29 — Josiah’s death at Megiddo.

- 2 Chronicles 35:20-24 — fuller account of Josiah and Pharaoh Neco.

- 2 Kings 23:31 — Jehoahaz’s age and the length of his reign.

- 2 Kings 23:31-34 — the deposition and exile.

- 2 Chronicles 36:1-4 — parallel account in Chronicles.

Read each passage aloud if you like, because the sound of the words will register what the mere outline does not.

Final thoughts, softly offered

At the end of the day, Jehoahaz is a reminder of the strange ways history chooses its focal points. Some kings turn into symbols and are dissected for centuries; others are margins condensed into a few sentences. This should teach you to be wary of equating long tenure with moral significance or short tenure with insignificance. Lives are not measured merely by length or notice; they are measured by the web of relations they participate in.

There’s also a kind of loneliness that clings to these short reigns. If you’ve ever felt like a stop-gap in someone else’s life — that you were there to fill a weekend, a job, a role until something “meaningful” came along — then Jehoahaz is your ancient companion. The Bible does not immortalize him, but it does not erase him completely. It puts him on the page, briefly, so you can see the world in miniature — the terse interplay of personal claim and geopolitical command.

You’ll leave these verses with a mixture of pity and indifference: pity for a young man taken in chains, indifference because history had other, louder names to pronounce. That mixture is fitting. It keeps you sensible about the paradox that human lives are both fragile and consequential in ways that the archive cannot always make visible.

Explore More

For further reading and encouragement, check out these posts:

👉 7 Bible Verses About Faith in Hard Times

👉 Job’s Faith: What We Can Learn From His Trials

👉 How To Trust God When Everything Falls Apart

👉 Why God Allows Suffering – A Biblical Perspective

👉 Faith Over Fear: How To Stand Strong In Uncertain Seasons

👉 How To Encourage Someone Struggling With Their Faith

👉 5 Prayers for Strength When You’re Feeling Weak

📘 Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery – Grace and Mercy Over Judgement

A powerful retelling of John 8:1-11. This book brings to life the depth of forgiveness, mercy, and God’s unwavering love.

👉 Check it now on Amazon

As a ClickBank Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Acknowledgment: All Bible verses referenced in this article were accessed via Bible Gateway (or Bible Hub).

“Want to explore more? Check out our latest post on Why Jesus? and discover the life-changing truth of the Gospel!”